On a Saturday in August, Lucia Rollow, who runs the Bushwick Community Darkroom, threw a launch party for her friend’s new brand of film: “Ready to dive into a world of creativity? Join us in celebrating the GRAIN Film launch this Saturday, August 26, from 5-8pm at Orchid House Studios!,” the announcement on Instagram read.

“It was a small event, but it was nice. Very chill and, like, positive,” she said. “You know, we took some beautiful photos in a beautiful studio. It was a beautiful film. We were just really excited about the fact there was going to be a new type of film available, because it seems like every time we turn around, Kodak or Fuji is discontinuing another speed,” referring to the different types of “film stocks” that have stopped being manufactured over the years.

On Monday, two days after the party, Rollow got an email from a film company called CineStill: “It has come to our attention that your company is releasing some new color films onto the market,” the email read. “While any new release is great for the analog photographer and we ourselves celebrate new additions to the market, we noticed some improper usages of our trademarks and wanted to address them as soon as we could, for as little impact and inconvenience as possible, while also performing our due diligence to uphold our trademarks.”

“Any products that use our established trademarks must be named something else in order not to be flagged by our legal team,” the email said. “We would hope to handle this before they deem it necessary to get involved, which is why we have sent this message as a courtesy.”

Rollow said the email "really kind of took the wind out of our sails," and that Bushwick Community Darkroom "kind of just went silent for a little while because we didn't want to do anything else that would get them to actually file a lawsuit."

Rollow didn’t know it then, but other tiny companies had been getting similar notices from CineStill, which popularized a type of film called 800T and helped drive a resurgent interest in film photography. The company was suddenly threatening a handful of upstart companies, people selling film from their bedrooms, and community darkrooms, because they are selling competitors’ film that CineStill believes violates its 800T trademark.

Over the last week, these legal threats have become public and have backfired spectacularly, as CineStill, a formerly beloved company, is pissing everyone off in a notoriously tiny, tight-knit community of analog photography. “StopBuyingCineStill” has become a rallying cry on Instagram and among small companies and photographers. The r/AnalogCommunity subreddit is full of memes and rallying cries telling people to boycott CineStill’s film because of its overzealous trademark enforcement.

The people who have been threatened by CineStill say they have to choose between blindly complying with CineStill’s requests and paying for lawyers they cannot afford to challenge them.

The community is even more shocked that CineStill has chosen perhaps the worst possible public relations strategy and has decided to post through it. The company is actively beefing with people who are posting about it on social media, and told me in an email that the small businesses they threatened “have been intentionally trying to tarnish our reputation and use this as an opportunity to potentially gain market share.”

“They are fabricating stories and participating in unfair competition in order to hurt our business and have made up claims of behavior that we have not actually engaged in, in order to tarnish our reputation,” Steve Carter, CineStill’s head of marketing and outreach, wrote to me. “It is illegal. And ethically wrong.”

I’ve spent the last week talking to lawyers, academics, and photographers about CineStill and the fiasco that has unfolded. I am relatively new to the film photography world, but I have written extensively about copyright and trademark law, and am familiar with tactics used by companies like Nintendo, for example, to protect their intellectual property. CineStill is not a corporate behemoth, though. It is a relatively small company founded in 2012 in Los Angeles and to this day only has about a dozen employees. CineStill is not Kodak or Fuji, but it is a large player in the film photography world.

I decided to report this story because the tactics being deployed by CineStill seemed incredibly counterproductive. This story is relatively technical and requires a bit of explanation about specific types of film and also requires diving into the nuts and bolts of trademark law. But I’ve been transfixed by it particularly because I have never seen a company lose goodwill among their customers so thoroughly and quickly. To be clear, this is currently essentially the only thing that the film photography community is talking about right now.

Last week, the photography blog PetaPixel covered this saga and framed it as CineStill being “swarmed by an angry mob stoked by misinformation.” But the small business owners I spoke to say that they feel their businesses have been legitimately threatened, and law professors I spoke to said that the situation isn’t a straightforward one.

“A comment on one of my social media posts said ‘It’s like CineStill took a college class in how to tank their brand,’” Rollow told me. “That about sums it up.”

CineStill became a major and respected player in the film photography world because it commercialized a process in which film for shooting motion pictures could be turned into film for shooting still photography. This came at a time when there was worry that, eventually, Kodak and Fuji would stop making film for still cameras, and so the community quickly embraced it.

To do this, CineStill used a chemical process that removes the “RemJet” layer from Kodak motion picture film (this is called a “pre bath,” meaning it’s a process done before the film is used to take pictures). The RemJet layer is a black coating used on motion picture film that protects it when used at high speeds in video cameras. The RemJet layer is not only unnecessary if you’re going to use it for still photography, but also makes developing the film messier, more difficult, and requires a different chemical process than developing normal color film, called C-41. With the RemJet layer removed, motion picture film can be shot and developed like normal C-41 film.

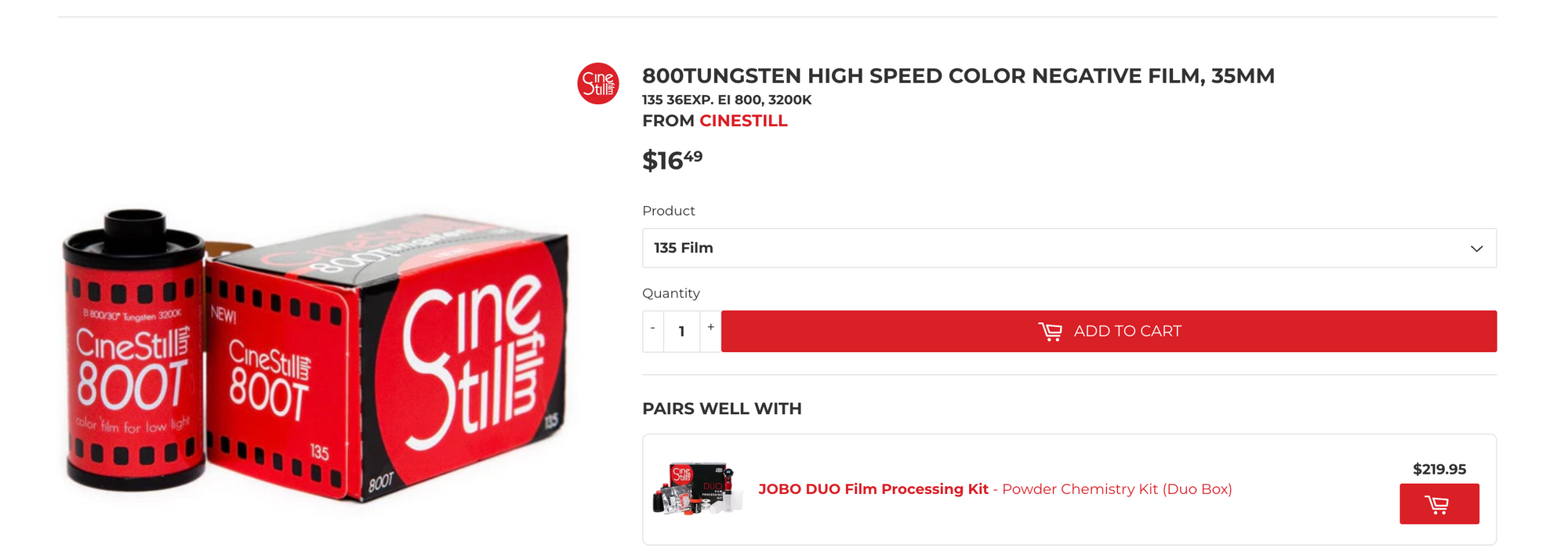

CineStill did not invent the concept of removing the RemJet layer from film. DIY Chemical recipes and instructions published by Kodak itself have gone viral in the community during this ongoing saga. But CineStill did commercialize and popularize the process using a type of Kodak motion picture film called 500T. CineStill’s most popular product, and the one at issue now, is a film stock called “800T,” which refers to the film’s ISO (800) and the fact that it is “tungsten balanced,” meaning it can accurately recreate colors under tungsten light sources (incandescent bulbs, low light situations, etc).

Basically, CineStill 800T film creates extremely vibrant, accurate color reproduction in low-lighting situations, and the film has become really popular since its release. This is an example of the type of image that's popular to take with CineStill 800T:

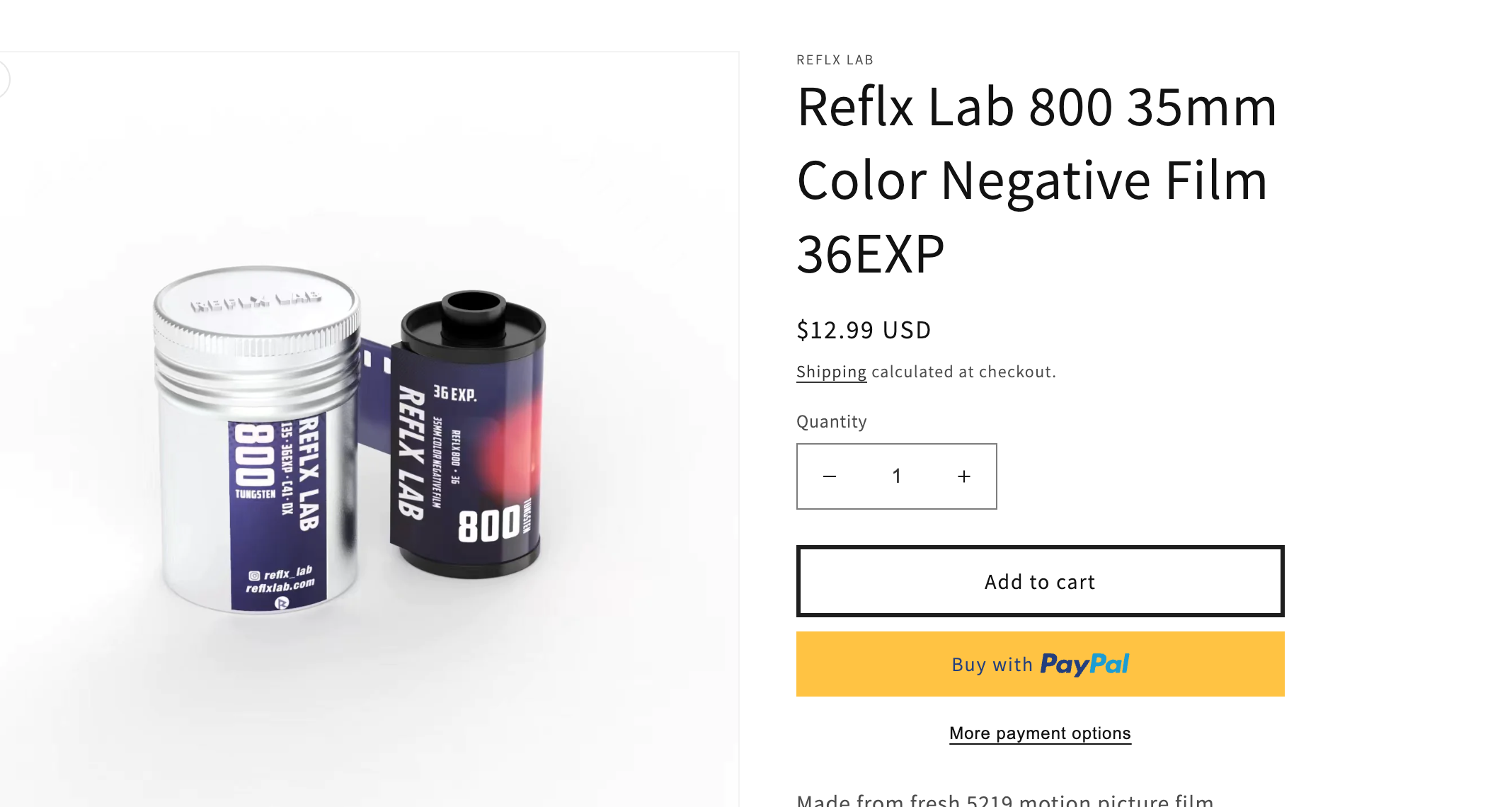

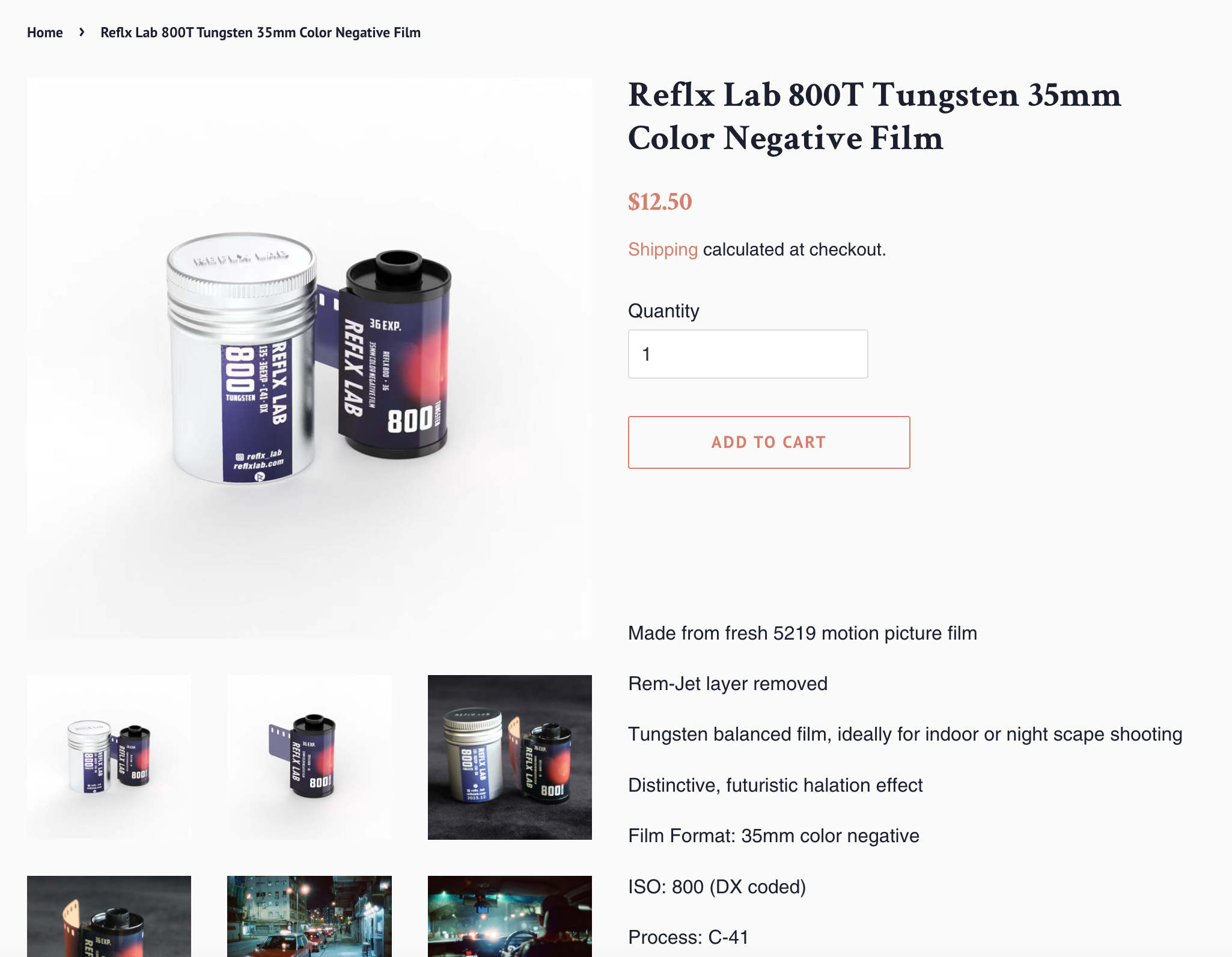

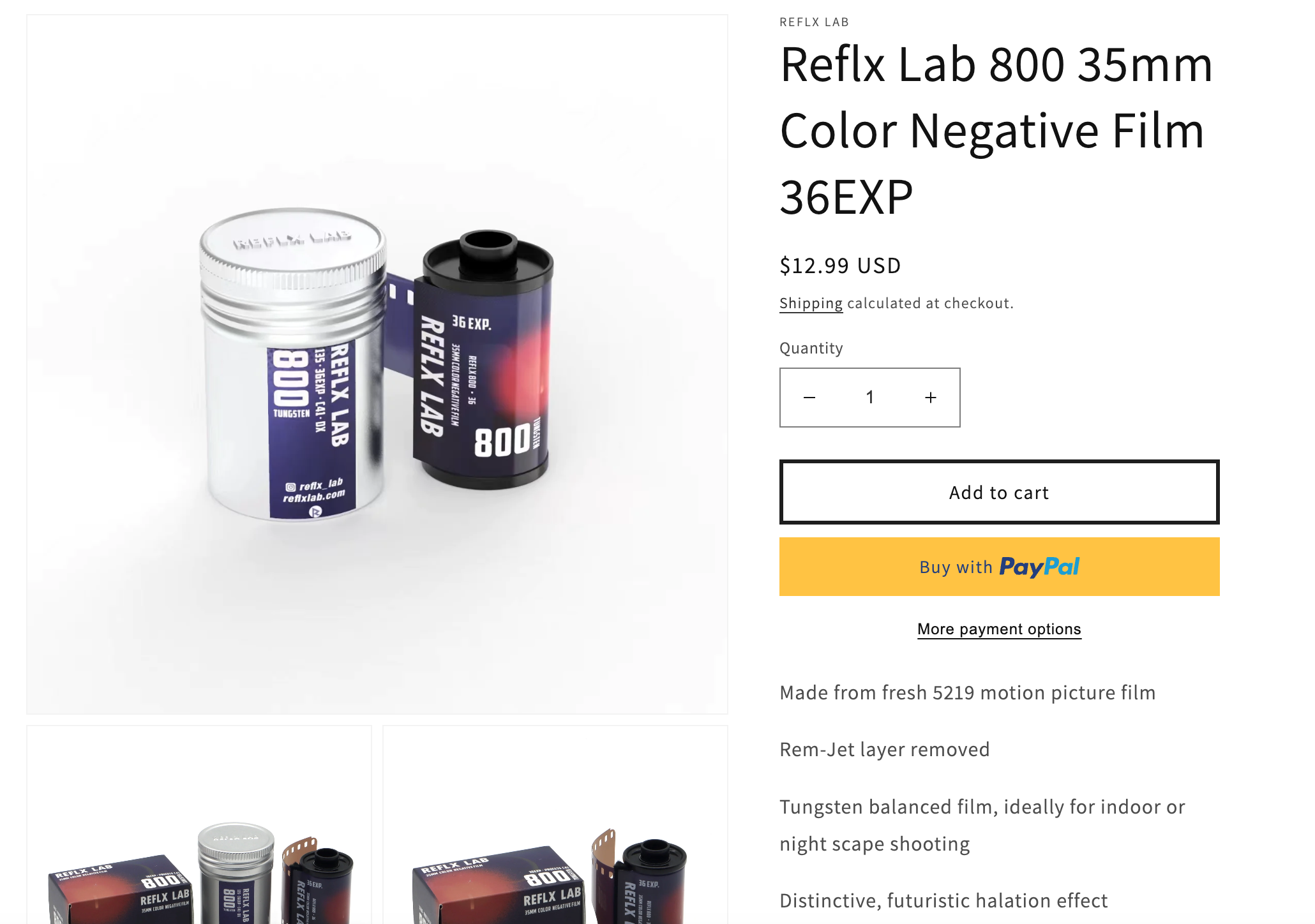

Since then, various other companies have made similar types of film in which the RemJet layer has been removed from motion picture film for still photographers. Most of these companies have undercut CineStill on price. A Shenzhen, China-based company called Reflx Labs, for example, sells a popular alternative for a few dollars less per roll. A company called Amber sells similar, as does Grain, the company who Rollow threw a release party for.

Here's what the packaging looks like, side by side:

Note: These images are intended to show the packaging only, not the ecommerce listings. Reflx's listing has varied over time.

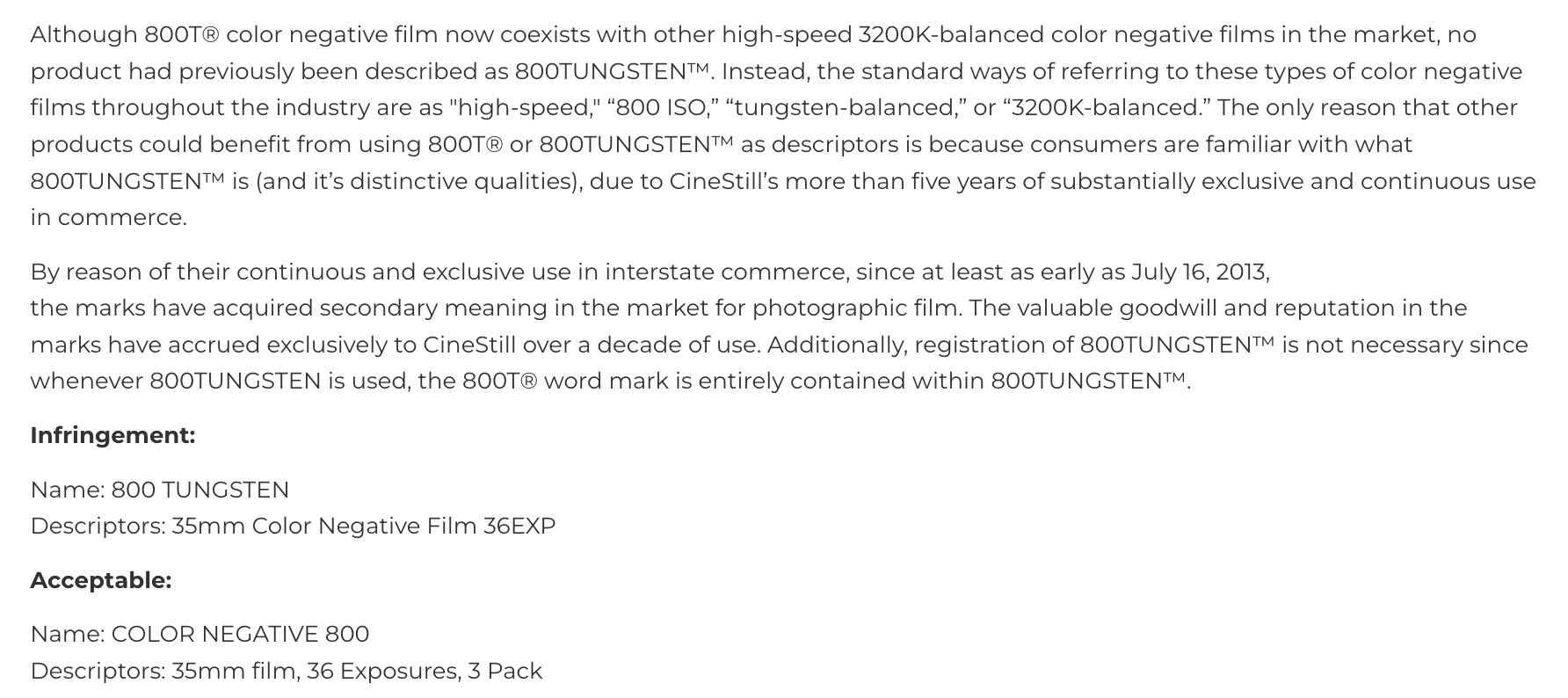

“800T” describes what the film is. It is 800 ISO, tungsten-balanced film, which are terms that anyone buying the film would understand and would want to know. In the 1990s, Kodak sold a motion picture film called Vision 800T, which is no longer in production (and whose trademark has been abandoned). An information card from Kodak’s film states “With an exposure index of 800 in tungsten light, this is the world’s fastest color negative motion picture film.” Despite the descriptive nature of the term, in September 2022, CineStill got a trademark from the US Patent and Trademark Office for “800T” and “800TUNGSTEN.” CineStill has a lengthy “Trademark Policy” on its website that explains what is believes are acceptable and unacceptable naming conventions for similar films:

None of the packaging for these competing films looks like CineStill’s packaging, but at some point, all of these films have called their film “800T” or “T800” or “800 Tungsten,” or used those descriptors in their listings.

Over the last few months, Reflx has tweaked its website listing to remove the letter ‘T.’ Here is Reflx’s listing from last year compared to now:

Left: Listing from 2022. Right: Listing from now

Reflx Lab did not respond to a request for comment.

And Grain has removed the letter ‘T’ from its box. On Instagram, John Singh Bhatia, the creator of Grain, wrote “We want to make entering into film photography easier and improve its user experience while also providing progress for our craft. Much of that has been halted recently by CineStill.”

“Initially we kept this quiet because we couldn’t battle them nor did we want to start a larger issue with a company we admired,” he wrote. “However, we now realize how many other companies they also did this to. And is the only reason we are speaking out. We do not want to point blame nor do we want to cause distrust. We are simply sharing our story the way many other companies bravely have. It’s unfortunate and saddening to know how walled and gated Cinestill wants to keep the film world. It’s not right nor should it be allowed. The communication Cinestill sent us was to stop our sale and growth of film forcing us to spend thousands of dollars and hours more to rebrand our film which we were so proud of.”

In the comments of that post, CineStill wrote that “if you had replied to us directly after we notified you, we would have been happy to compromise by offering a sell-off period for packaging already in existence, like we did with several others who we worked with, for the same products coming out of China that you are offering, to correct the mistake.” CineStill then posted the letter that it sent to Bushwick Community Darkroom’s Lucia Rollow, who is not involved in actually making Grain film (but did forward the communication to Bhatia).

These competing films are designed to be similar: There are very few factories that still actually manufacture film, and the widespread belief is that all 800T films are Kodak Vision 3 500T motion picture film that has had the RemJet layer removed, though there may be variations in how the RemJet layer is removed, how the film is rolled into canisters, and differences in the packaging. There are endless debates about the pros and cons of shooting Reflx vs CineStill vs Amber, the different look and feel of the final images you get with each, etc. Basically, we are not talking about “counterfeit” CineStill, but about truly competitive products, what they can be called, how they can be advertised, and who can sell them.

Pino Shah is a photographer who sells film on the side from his one bedroom apartment “that is my office, my shop, and my warehouse.” Shah sells CineStill film, but also sells Reflx Lab’s film. In May, he told me that he “made some foolish choices in regards to unwittingly infringing on CineStill’s trademark for the 800T film.” On his eBay, Etsy, and Shopify listings for Reflx film, “I referred to [Reflx film] as 800T and compared it to CineStill 800T film. The CineStill team contacted eBay, Etsy, and Shopify and had my listings taken down,” he told me. “It felt a bit extreme given that we had a working relationship. I sell their products. I thought I was simply giving folks a choice—here is a premium brand and here is a less expensive brand.”

“He’s just a guy! In his fucking bedroom, making a couple extra bucks”

Shah said that Reflx eventually modified its packaging and he started selling their film again with a modified item description. “Last week, my listing on eBay got suspended again. I got a final warning from eBay. That shook me up,” he said. “I have been on eBay for over 20 years and have over 600 5-star ratings.” Shah said he went back and forth with CineStill and was eventually able to get them to withdraw the strike against his account, but that the entire situation made him realize how fragile his business is. He posted about his experience on Reddit “as I was still stressed out and anxious and felt that perhaps, someone in the analog film community would share their experience with something similar.” He was right. The post went viral, and other small business owners began coming forward about their experiences with CineStill.

In its email to me, CineStill said that it is chalking up the problem to “What started as a misunderstanding between CineStill and one other small business owner who was understandably overwhelmed by the complexities of trademark law, led him to seek legal advice on the Reddit platform,” seemingly referring to Shah’s initial post (the company did not respond to a follow up email asking for more specifics). “This gave an opportunity for some other competing businesses to take advantage of the confusion and target us with fabrications to damage our business and reputation. This only magnified the initial confusion and turned it into outrage on Reddit due to misunderstanding of trademark law, lack of knowledge of our manufacturing capabilities, and general miscommunication.”

Omer Hecht owns a film processing and analog photography store called CatLabs in Boston. Last week, he published a post on the store’s blog called “We got Sued by Cinestill :(,” after seeing Shah’s post. Hecht said he originally wasn’t going to post anything, but after seeing Shah’s post, decided to speak up about his own experience with CineStill: “He’s just a guy! In his fucking bedroom, making a couple extra bucks,” he said.

Hecht got a letter and, later, a cease-and-desist notice from CineStill for selling Reflx 800T-branded film, and is fighting back with his own lawyers. It’s important to note that CineStill has not actually filed a lawsuit against him, but their lawyers have exchanged letters: “They’re characterizing it as like, polite emails, where they politely ask that we comply. And at the bottom of the email, they also said, you know, if you don’t comply, our legal team is standing by to take legal action against you. So it’s a pending, open legal matter that has cost us thousands and thousands of dollars responding to.”

“The whole argument of the trademark seemed irrational to me as a layperson,” Hecht said. “So I said, ‘Fuck it, I’ll send it to a lawyer, let the lawyers deal with it.’ The risk is too big for me to take a chance on.”

When I asked CineStill about Hecht and his blog post, they stressed that they did not actually sue him. They also added this: “He has deliberately spread unfounded rumors within the industry, and instigated a conflict by infringing on our trademarks and forcing us to talk to his lawyer when we reached out with a courtesy notice to inform him of how to resolve the issues without cost or business interruption. Now he is claiming that we sued him and many other small businesses around the world, which is completely false. He and others with a similar jealousy are fabricating stories and participating in unfair competition in order to hurt our business and have made up claims of behavior that we have not actually engaged in, in order to tarnish our reputation.”

Hecht told me he did not know exactly what CineStill was talking about, and CineStill did not respond to my request for it to elaborate. Hecht said he does not consider himself a competitor of CineStill: “I think we operate in completely separate fields,” he said. “I don’t think we’re competitors. In fact, for the longest time, we’ve been trying to sell their product.”

Hecht said he finds the entire situation ridiculous: “This is such a tiny little business market, from the perspective of revenue, we’re talking minuscule numbers,” he said. Selling film “is not a money making scheme, but it’s something we like to do, because it complements our business as a whole.”

A 'Descriptive' Trademark

CineStill itself says that it has no legal problem with the fact that Reflx and Amber and Grain sell 800 ISO, tungsten-balanced film. Law professors told me they think that CineStill choosing to enforce its trademark on the “800T” terminology by going after tiny retailers of film because of poor legal advice and is a bad public relations strategy based on statements I sent to them from CineStill.

“For the last year, we’ve seen our trademarks wrongly used on products imported from China for both packaging and marketing purposes, either by using our registered trademarks for the product names or for statements like ‘same as CineStill’ and ‘better than 800T’ to help sell these products,” Carter of CineStill told me. “Our legal counsel informed us that we must do the minimum required to protect our trademarks or they will eventually lose their distinctiveness as source identifiers. CineStill’s team (not lawyers) first sent courtesy notices via email, not cease and desist letters, to apparent trademark infringers to address concerns about the confusing similarity of certain products and their violation of trademarks that CineStill legally owns. Only a couple of individuals responded poorly to our initial courtesy notices by referring us to their legal representation, who demanded that our lawyers contact their lawyers directly to send a formal Cease and Desist.”

Simply put: comparative advertising using terms like “same as CineStill” and “better than 800T” are legal, and a time-honored promotional strategy. Telling retailers that they cannot advertise a different product as “better than 800T” is “flat out bogus,” according to Aaron Perzanowski, an intellectual property expert at the University of Michigan Law School.

“That’s absolutely lawful comparative advertising, and no trademark owner has the right to prevent it,” he said. “Coke can’t sue Pepsi for trademark infringement over the Pepsi challenge. And Verizon can’t sue AT&T under a trademark theory if they say their network is more reliable. Threatening people who make comparative claims has nothing to do with safeguarding the distinctiveness of your trademark. And if those are really the uses they are targeting, everyone should tell them to go pound sand.”

“You go to CVS, and there’s a CVS home brand thing that will say ‘comparable to a name brand.’ It says it right on the fucking box, right, and it’s legal for CVS to do that on the same shelf next to the name brand product,” Hecht said. “It’s legal for CVS to do that, so why would CineStill have a claim here?”

Rebecca Tushnet, a legal scholar who specializes in trademark law at Harvard Law School, also said that the argument that CineStill simply had no choice but to try to enforce its trademark is one that trademark holders often make but that rarely holds water: “Trademark owners love to say this, because it’s like ‘It’s not my fault, I had to do it. I’m not a bully, I’m just doing what the law demands,’” she said.

Sarah Burstein, who studies the intersection of intellectual property law and art at Suffolk University, told me that so called “trademark bullies” often feel they have a “duty to police” their trademarks. A legal paper about the issue call this duty "vague" and says that the "uncertain duty renders trademark owners unable to accurately predict the risk of harm that third parties pose to their trademarks. Secondly, inherent cognitive biases affecting evaluations of such risk lead to systematic judgment errors and overestimation of the risk involved, thereby encouraging aggressive trademark enforcement."

Both Burstein and Tushnet pointed out (as have many in the photography community) that CineStill’s initial application for a trademark on 800T was rejected by the Trademark Office because it was “merely descriptive: In the present case, the mark is 800T, and the goods are ‘Unexposed photographic film,’” the Trademark Office wrote. “Considering that the mark refers to film with an 800 ISO rating and which utilizes tungsten, the mark is descriptive of the photographic film goods and cannot be registered.”

CineStill’s lawyers challenged this determination and eventually won recognition of the trademark by arguing for a “Claim of Acquired Distinctiveness, based on Five or More Years' Use.”

Burstein said that it is entirely possible that, because 800T literally describes what the film is, it would be an interesting case for a court to review.

“I think if you were to bring this claim in Federal Court, you’d expect defendants to make a defense that it’s merely descriptive language,” Burstein said. “When we’re deciding an issue of trademark infringement, it’s not just ‘Are you using these letters on this product.’ You look at the entire context, you look at the mark in situ. If you have your own separate mark next to it, in some cases, that can make a big difference, especially if you have a weaker mark. I think this looks like a weaker mark,” meaning it is less well-known. “The ultimate issue is whether the consumer would be confused.”

What Now?

It’s not clear what happens now. CineStill has insisted in social media comments, emails to users, and an email to me that it doesn’t want to sue anyone. On the other hand, a company that everyone agrees makes a good product has completely frittered away all of the goodwill it created by going after anyone using “800T” in a way it didn’t like online.

Some film stores have said they will stop carrying CineStill, people have begun posting how to make your own version of RemJet-removed film, and anti CineStill posts have repeatedly gone viral on Reddit and Instagram. Others have pointed out that giant retailers like Urban Outfitters and B&H Photo sell CineStill competitors, with 800T branding.

“I’m just thinking: ‘What are you doing? Don’t you have a business to run?,” Rollow said about hearing of all the cease-and-desist letters. “One of my friends was just saying that CineStill’s behavior is giving hardcore jobless and hobbyless vibes. I thought that was hilarious. It’s like, they’re a fucking loser in their mom’s basement trolling the internet when they’re meant to be a fairly large sized corporation. They should have better things to do than send me a cease and desist.”

I asked Hecht what he thought CineStill should have done: “You say, ‘Our product is better and that’s all that matters,” he said.