Reverse engineer Scotty Allen made his own iPhone. Well, more accurately, he made his own iPhone enclosure out of a block of aluminum, put the internal components of an iPhone into it, and managed to make it all work. Then, he used the same schematics he made to 3D print a working iPhone enclosure out of nylon carbon fiber.

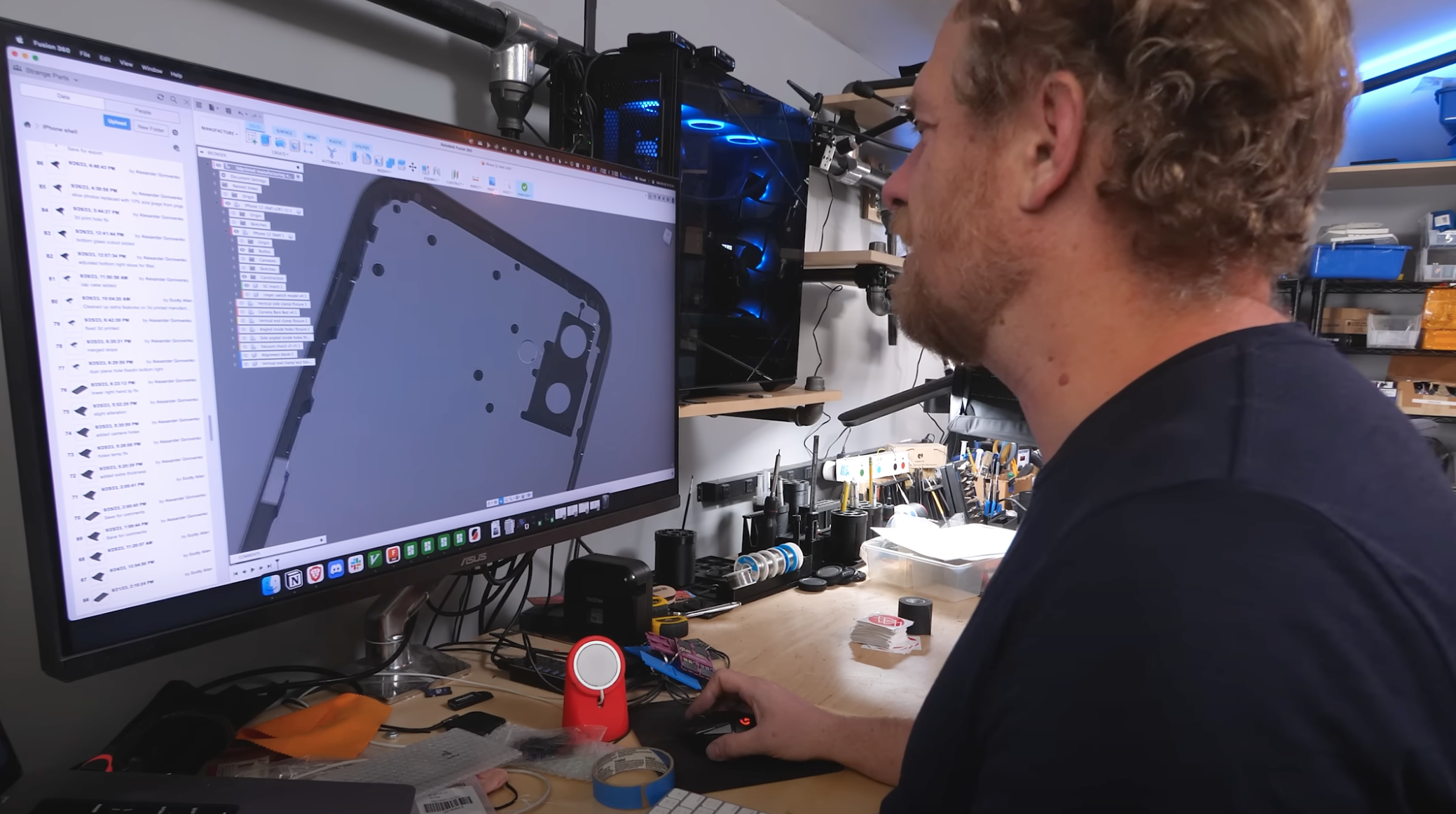

Like lots of repair and DIY projects on the iPhone, Allen did tons of painstaking work over the course of a year to more or less recreate something that already exists and that most people do not need. But his work opens the door to a more modifiable iPhone and a DIY culture around smartphones that still doesn’t really exist. Essentially, he took a block of aluminum, used a CNC mill to carve it down, and was able to put all of the components in the custom enclosure, the way someone might when they’re building a PC. Along the way, he made CAD files of the inside of an iPhone, which will allow people to recreate his work. It is now possible to download his design files and 3D print your own iPhone shell.

“There's been an open question for me from the beginning, which is like, we have this culture around modding PCs, right? And custom PCs. Why do we not have that for phones?,” Allen told me in a video chat. “It’s very celebrated in the culture. But then when you talk about building your own phone, everyone is like, ‘No, that’s crazy.’ Apple is going to sue you.”

As you might expect, the iPhone’s enclosure is not just an empty block of metal. There are various tiny holes for screws and engraved areas for cables and antennas to go. Allen studied all of this and, through a roughly year-long process of trial-and-error, was able to recreate this enclosure and create blueprints for other people to replicate it.

“This was really difficult because I had to reverse engineer it and there was a lot of time spent figuring out, ‘OK, now I’ve got it drawn, but how do I know everything about the interior walls? There’s all these little threaded inserts that are glued in. And I think I actually went about this machining it in a different way than Apple does,” he said.

Over the years, Allen has done lots of cool things with the iPhone, which started with adding a working headphone jack back into the iPhone 7 after Apple removed it. He is part of the right to repair movement, but takes things a step further and says he’s advocating for the right to modify, and the normalization of opening and tweaking things like the iPhone to prove that they’re not just unknowable black boxes.

“I look at this as an infrastructure project, which is, let’s make a 1-to-1 copy,” he said. “It’s not totally 1-to-1, but in terms of overall geometry, it’s a fairly faithful representation and reproduction with the goal that, if you want to do interesting things, you need to start with the boring things first. And now with all the design files that I’ve created, you can really easily begin to modify it to look how you want on the outside, to add space for things on the inside. So this is a base for doing all sorts of more creative things.”

Allen said that at the moment one challenge is that there are limitations on the types of touchscreens that will work with the iPhone, but that with more work it would be possible to work with additional modifications.

“My notion is that a phone is a device that you can open up and tinker with, or at least repair,” he said. “I think I’ve had a hand in saying, ‘Look, this isn’t a black box that only Apple is allowed to open.’ … I think consistently what I’ve done is poke at the edges and say, ‘What other things can we do with this?’”