Movies are supposed to transport you places. At the end of last month, I was sitting in the Chinese Theater, one of the most iconic movie theaters in Hollywood, in the same complex where the Oscars are held. And as I was watching the movie, I found myself transported to the past, thinking about one of my biggest regrets. When I was in high school, I went to a theater to watch a screening of a movie one of my classmates had made. I was 14 years old, and I reviewed it for the school newspaper. I savaged the film’s special effects, which were done by hand with love and care by someone my own age, and were lightyears better than anything I could do. I had no idea what I was talking about, how special effects were made, or how to review a movie. The student who made the film rightfully hated me, and I have felt bad about what I wrote ever since.

So, 20 years later, I’m sitting in the Chinese Theater watching AI-generated movies in which the directors sometimes cannot make the characters consistently look the same, or make audio sync with lips in a natural-seeming way, and I am thinking about the emotions these films are giving me. The emotion that I feel most strongly is “guilt,” because I know there is no way to write about what I am watching without explaining that these are bad films, and I cannot believe that they are going to be imminently commercially released, and the people who made them are all sitting around me.

Then I remembered that I am not watching student films made with love by an enthusiastic high school student. I am watching films that were made for TCL, the largest TV manufacturer on Earth as part of a pilot program designed to normalize AI movies and TV shows for an audience that it plans to monetize explicitly with targeted advertising and whose internal data suggests that the people who watch its free television streaming network are too lazy to change the channel. I know this is the plan because TCL’s executives just told the audience that this is the plan.

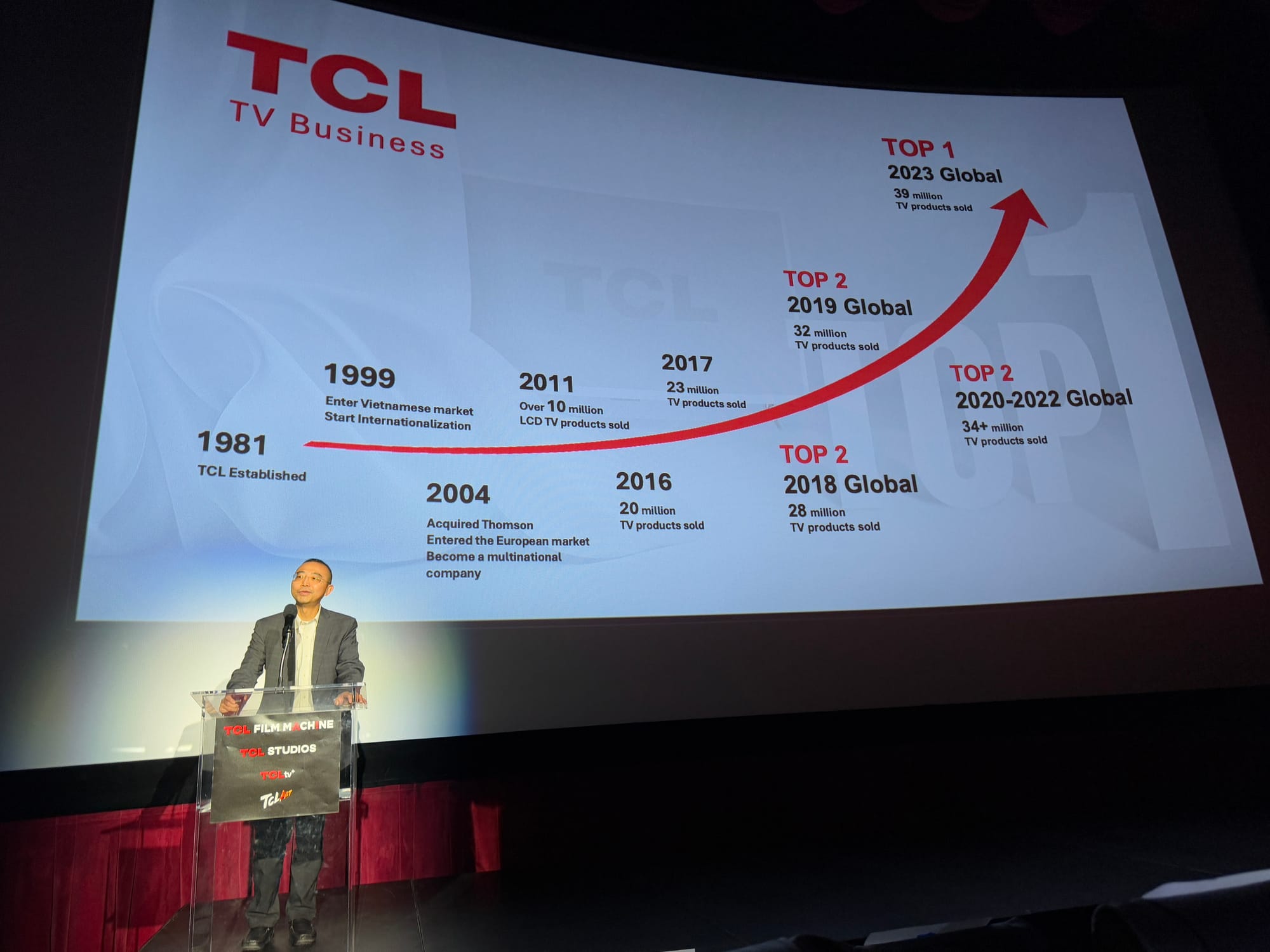

TCL said it expects to sell 43 million televisions this year. To augment the revenue from its TV sales, it has created a free TV service called TCL+, which is supported by targeted advertising. A few months ago, TCL announced the creation of the TCL Film Machine, which is a studio that is creating AI-generated films that will run on TCL+. TCL invited me to the TCL Chinese Theater, which it now owns, to watch the first five AI-generated films that will air on TCL+ starting this week.

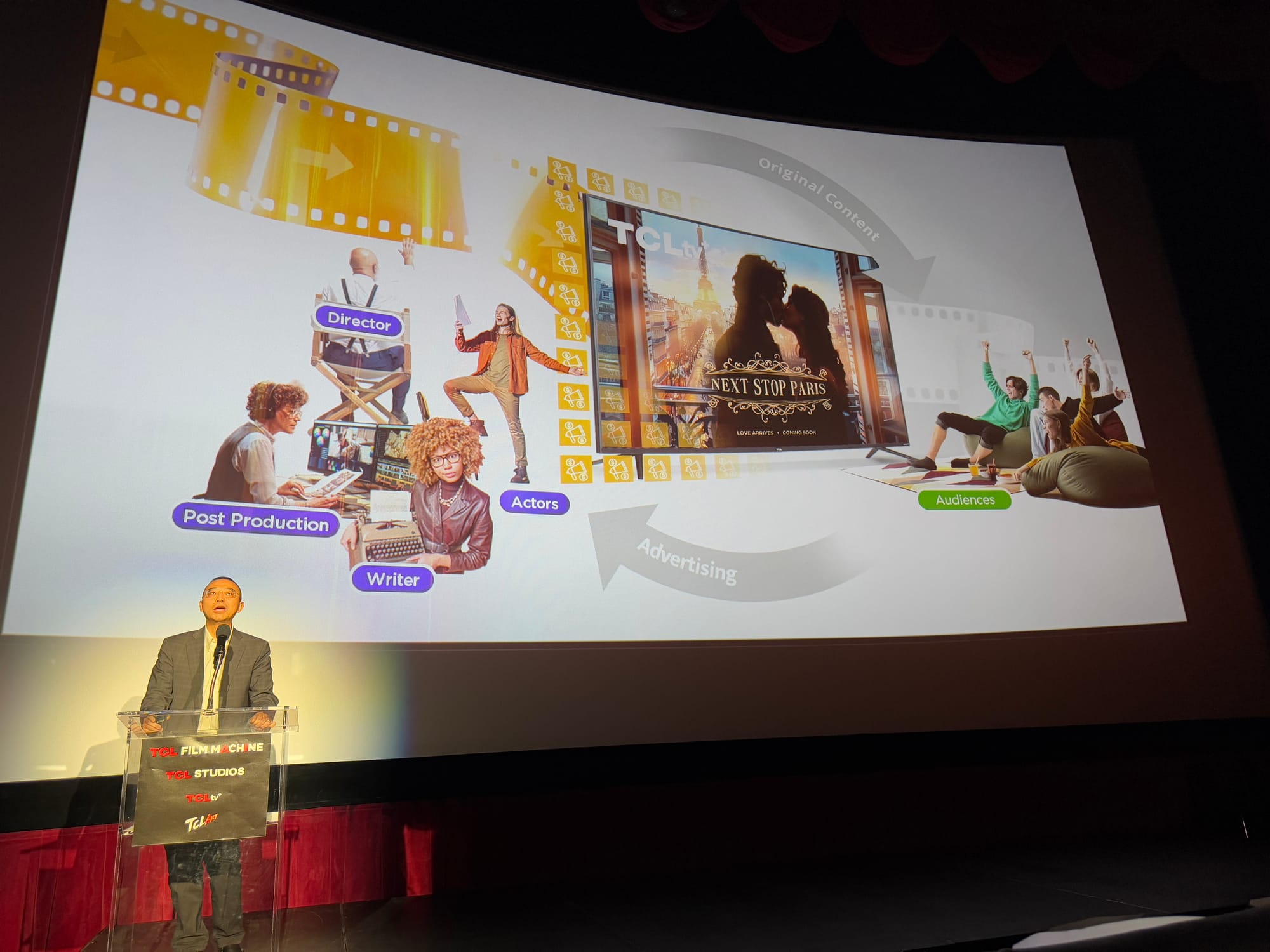

Before airing the short, AI-generated films, Haohong Wang, the general manager of TCL Research America, gave a presentation in which he explained that TCL’s AI movie and TV strategy would be informed and funded by targeted advertising, and that its content will “create a flywheel effect funded by two forces, advertising and AI.” He then pulled up a slide that suggested AI-generated “free premium originals” would be a “new era” of filmmaking alongside the Silent Film era, the Golden Age of Hollywood, etc.

Catherine Zhang, TCL’s vice president of content services and partnerships, then explained to the audience that TCL’s streaming strategy is to “offer a lean-back binge-watching experience” in which content passively washes over the people watching it. “Data told us that our users don’t want to work that hard,” she said. “Half of them don’t even change the channel.”

“We believe that CTV [connected TV] is the new cable,” she said. “With premium original content, precise ad-targeting capability, and an AI-powered, innovative engaging viewing experience, TCL’s content service will continue its double-digit growth next year.”

Starting December 12, TCL will air the five AI-generated shorts I watched on TCL+, the free, ad-supported streaming platform promoted on TCL TVs. These will be the first of many more AI-generated movies and TV shows created by TCL Film Machine and will live alongside “Next Stop Paris,” TCL’s AI-generated romcom whose trailer was dunked on by the internet.

The first film the audience watched at the Chinese Theater was called “The Slug,” and it is about a woman who has a disease that turns her into a slug. The second is called “The Audition,” and it is kind of like an SNL digital short where a real human actor goes into an acting audition and is asked to do increasingly outrageous reads which are accomplished by deepfaking him into ridiculous situations, culminating in the climax, which is putting the actor into a series of famous and copyrighted movie scenes. George Huang, the director of that film, said afterward he thought putting the actor’s face into iconic film scenes “would be the hardest thing, and it turned out to be the easiest,” which was perhaps an unknowing commentary on the fact that AI tools are surreptitiously trained on already-existing movies.

“Sun Day” was the most interesting and ambitious film and is a dystopian sci-fi where a girl on a rain planet wins a lottery to see the sun for the first time. Her spaceship explodes but she somehow lives. “Project Nexus” is a superhero film about a green rock that bestows superpowers on prisoners that did not have a plot I could follow and had no real ending. “The Best Day of My Life” is a mountaineering documentary in which a real man talks about an avalanche that nearly killed him and led to his leg being amputated, with his narrated story being animated with AI.

All of these films are technically impressive if you have watched lots of AI-generated content, which I have. But they all suffer from the same problem that every other AI film, video, or image you have seen suffers from. The AI-generated people often have dead eyes, vacant expressions, and move unnaturally. Many of the directors chose to do narrative voiceovers for large parts of their films, which is almost certainly done because when the characters in these films do talk, the lip-synching and facial expression-syncing does not work well. Some dialogue is delivered with the camera pointing at the back of characters’ heads, presumably for the same reason.

Text is often not properly rendered, leading to typos and English that bleeds into alien symbols. Picture frames on the wall of “The Slug” do not have discernible images in them. A close up on a label of a jar of bath salts in the movie reads “Lavendor Breeze Ogosé πy[followed by indecipherable characters].” Scenery and characters’ appearances sometimes change from scene to scene. Scenery is often blurry. When characters move across a shot they often move or glide in unreal ways. Characters give disjointed screams. In “The Slug,” there is a scene that looks very similar to some of the AI Will Smith pasta memes. In “The Best Day of My Life,” the place where the man being buried under an avalanche takes refuge changes from scene to scene and it seems like he is buried in a weird sludge half the time. In “Sun Day,” the only film that really tried to have back-and-forth dialogue between AI-generated characters, faces and lips move in ways that I struggle to explain but which you can see here:

These problems—which truly do affect a viewer’s ability to empathize with any character and are a problem that all AI-generated media to date faces—were explained away by the directors not as things that are distracting, but as creative choices.

“On a traditional film set, the background would be the same, things would be the same [from scene to scene]. The wallpaper [would be the same],” Chen Tang, director of The Slug, said. “We were like ‘Let’s not do wallpaper.’ It would change a lot. So we were like, ‘How can we creatively kind of get around that, so we did a lot of close-up shots, a lot of back shots, you know tried to keep dialog to a minimum. It really adds to that sense of loneliness … so we were able to get around some of the current limitations, but it also helped us in ways I think we would have never thought of.”

A few weeks after the screening, I called Chris Regina, TCL’s chief content officer for North America to talk more about TCL’s plan. I told him specifically that I felt a lot of the continuity errors were distracting, and I wondered how TCL is navigating the AI backlash in Hollywood and among the public more broadly.

“There is definitely a hyper focused critical eye that goes to AI for a variety of different reasons where some people are just averse to it because they don't want to embrace the technology and they don't like potentially where it's going or how it might impact the [movie] business,” he said. “But there are just as many continuity errors in major live action film productions as there are in AI, and it’s probably easier to fix in AI than live action … whether you're making AI or doing live action, you still have to have enough eyeballs on it to catch the errors and to think through it and make those corrections. Whether it's an AI mistake or a human mistake, the continuity issues become laughter for social media.”

I asked him about the response to ‘Next Stop Paris,’ which was very negative.

“Look, the truth is we put out the Next Stop Paris trailer way before it was ready for air. We were in an experimental development stage on the show, and we’re still in production now,” he said. “Where we've come from the beginning to where we are today, I think is wildly, dramatically different. We ended up shooting live action actors incorporated into AI, doing some of the most bleeding-edge technology when it comes to AI. The level of quality and the concept is massively changed from what we began with. When we released the trailer we knew we would get love, hate, indifference. At the same time, there were some groundbreaking things we had in there … we welcome the debate.”

In part because of the response to Next Stop Paris, each of the films I watched were specifically created to have a lot of humans working on them. The scripts were written by humans, the music was made by humans, the actors and voice actors were human. AI was used for animation or special effects, which allows TCL to say that AI is going to be a tool to augment human creativity and is here to help human workers in Hollywood, not replace them. These movies were all made over the course of 12 weeks, and each of them had lots of humans working on them in preproduction and postproduction. Each of the directors talked about making the films with the help of people assigned to them by TCL in Lithuania, Poland, and China, who did a lot of the AI prompting and editing. Many of the directors talked about these films being worked on 24 hours a day by people across the world.

This means that they were made with some degree of love, care, and, probably with an eye toward de-emphasizing the inevitable replacement of human labor that will surely happen at some studios. It is entirely possible that these films are going to be the most “human” commercially released AI films that we will see.

One of the things that happens anytime we criticize AI-generated imagery and video is that people will say “this is the worst it will ever be,” and that this technology will improve over time. It is the case that generative AI can do things today that it couldn’t a year ago, and that it looks much better today than it did a few years ago.

Regina brought this up in our interview, and said that he has already seen “quite a bit of progress” in the last few months.

“If you can imagine where we might be a year or 18 months from now, I think that in some ways is probably what scares a lot of the industry because they can see where it sits today, and as much as they want to poke holes or be critical of it, they do realize that it will continue to be better,” he said.

Making even these films a year or two ago would have been impossible, and there were moments I was watching where I was impressed by the tech. Throughout the panel discussion after the movie, most of the directors talked about how useful the tech could be for a pitch meeting or for storyboarding, which isn’t hard to see.

But it is also the case that TCL knew that these films would get a lot of attention, and put a lot of time and effort into them, and there is no guarantee that it will always be the case that AI-generated films will always have so many humans involved.

“Our guiding principles are that we use humans to write, direct, produce, act, and perform, be it voice, motion capture, style transfer. Composers, not AI, have scored our shorts,” Regina said at the screening. “There are over 50 animators, editors, effects artists, professional researchers, scientists all at work at TCL Studios that had a hand in creating these films. These are stories about people, made by people, but powered by AI.”

Regina told me TCL is diving into AI films because it wants to differentiate itself from Netflix, Hulu, and other streaming sites but doesn’t have the money to spend on content to compete with them, and TCL also doesn’t have as long of a history of working with Hollywood actors, directors, and writers, so it has fewer bridges to burn.

“AI became an entry point for us to do more cost-effective experimentation on how to do original content when we don’t have a huge budget,” he said.

“I think the differentiation point too from the established studios is they have a legacy built around traditional content, and they've got overall deals with talent [actors, directors, writers], and they're very nervous obviously about disrupting that given the controversy around AI, where we don't have that history here,” he added.

The films were made with a variety of AI tools including Nuke, Runway, and ComfyUI, Regina said, and that each directors’ involvement with the actual AI prompting varied.

I am well aware that my perspective on this all sounds incredibly negative and very bleak. I think AI tools will probably be used pretty effectively by studios for special effects, editing, and other tasks in a way that won’t be so uncanny and upsetting, and more-or-less agree with Ben Affleck’s recent take that AI will do some things well but will do many other things very poorly.

Affleck’s perspective that AI will not make movies as well as humans is absolutely true but it is an incomplete take that also misses what we have seen with every other generative AI tool. For every earnest, creative filmmaker carefully using AI to enhance what they are doing to tell a better story, there will be thousands of grifters spamming every platform and corner of the internet with keyword-loaded content designed to perform in an algorithm and passively wash over you for the sole purpose of making money. For every studio carefully using AI to make a better movie, there will be a company making whatever, looking at it and saying “good enough,” and putting it out there for the purpose of delivering advertising.

I can’t say for sure why any of the directors or individual people working on these films decided to work on AI movies, whether they are actually excited by the prospects here or whether they simply needed work in an industry and town that is currently struggling following a writers strike that was partially about having AI foisted upon them. But there is a reason that every Hollywood labor union has serious concerns about artificial intelligence, there is a reason why big-name actors and directors are speaking out against it, and there is a reason that the first company to dive headfirst, unabashedly into making AI movies is a TV manufacturer who wants to use it to support advertising.

“I just want to take the fear out of AI for people,” Regina said. “I realize that it's not there to the level that everyone might want to hold it up in terms of perfection. But when we get a little closer to perfection or closer in quality to what’s being produced [by live action], well my question to the marketplace is, ‘Well then what?’”

The most openly introspective of any of the directors was Paul Johansson, who directed the AI movie Sun Day, acted in One Tree Hill, and directed 2011’s Atlas Shrugged: Part I.

“I love giving people jobs in Hollywood, where we all work so hard. I am not an idiot. I understand that technology is coming, and it’s coming fast, and we have to be prepared for it. My participation was an opportunity for me to see what that means,” Johansson said. “I think it’s crucial to us moving forward with AI technology to build relationships with artists and respecting each craft so that we give them the due diligence and input into what the emerging new technology means, and not leaving them behind, so I wanted to see what that was about, and I wanted to make sure that I could protect those things, because this town means something to me. I’ve been here a long time, so that’s important.”

Midway through the AI movie Project Nexus, about the green rock, I found myself thinking about my high school classmate and all of the time he must have spent doing his movie’s special effects. Project Nexus careened from scene to scene. Suddenly, a character says, out of nowhere: “What the fuck is going on?” Good question.