For the last few months Instagram has served me a constant stream of ads for hard drugs, stolen credit cards, hacked accounts, guns, counterfeit cash, wholesale quantities of weed, and Cash App scams, as well as a Russian-language job posting seeking paid-in-cash massage therapists. Nearly all of these advertisements link directly to Telegram accounts where the drugs or illegal services can be directly purchased. With one tap, I was repeatedly taken from bouncing through Instagram stories of my friends on vacation to Telegram chat accounts where I could buy automatic weapons, meth, and stolen credit cards.

Besides being delivered directly to me by Instagram’s algorithm, thousands of these ads can be trivially found on Meta’s ad library by searching “t.me,” which is the link shortener for Telegram, exposing a massive content moderation and ad screening failure by the company.

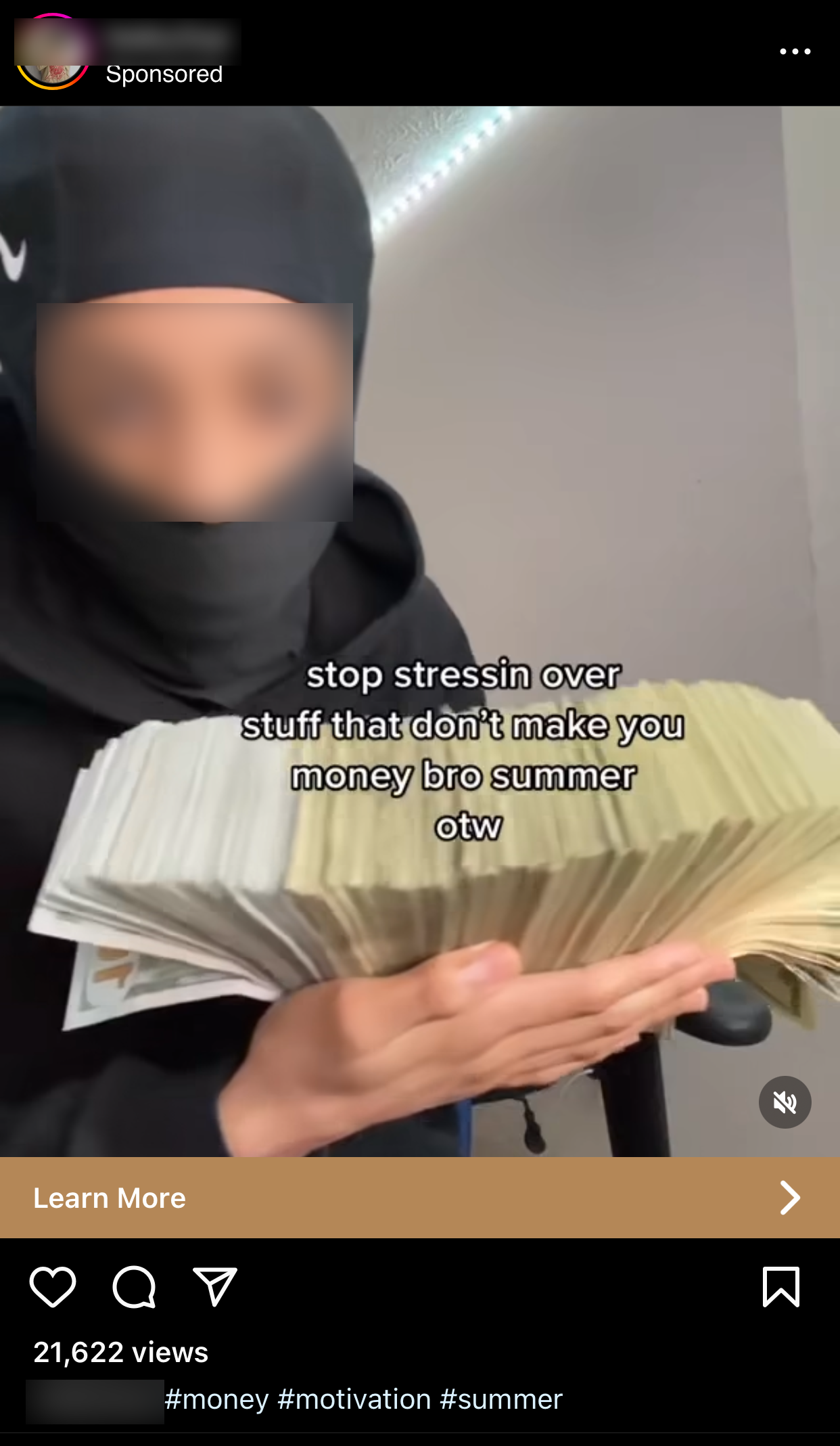

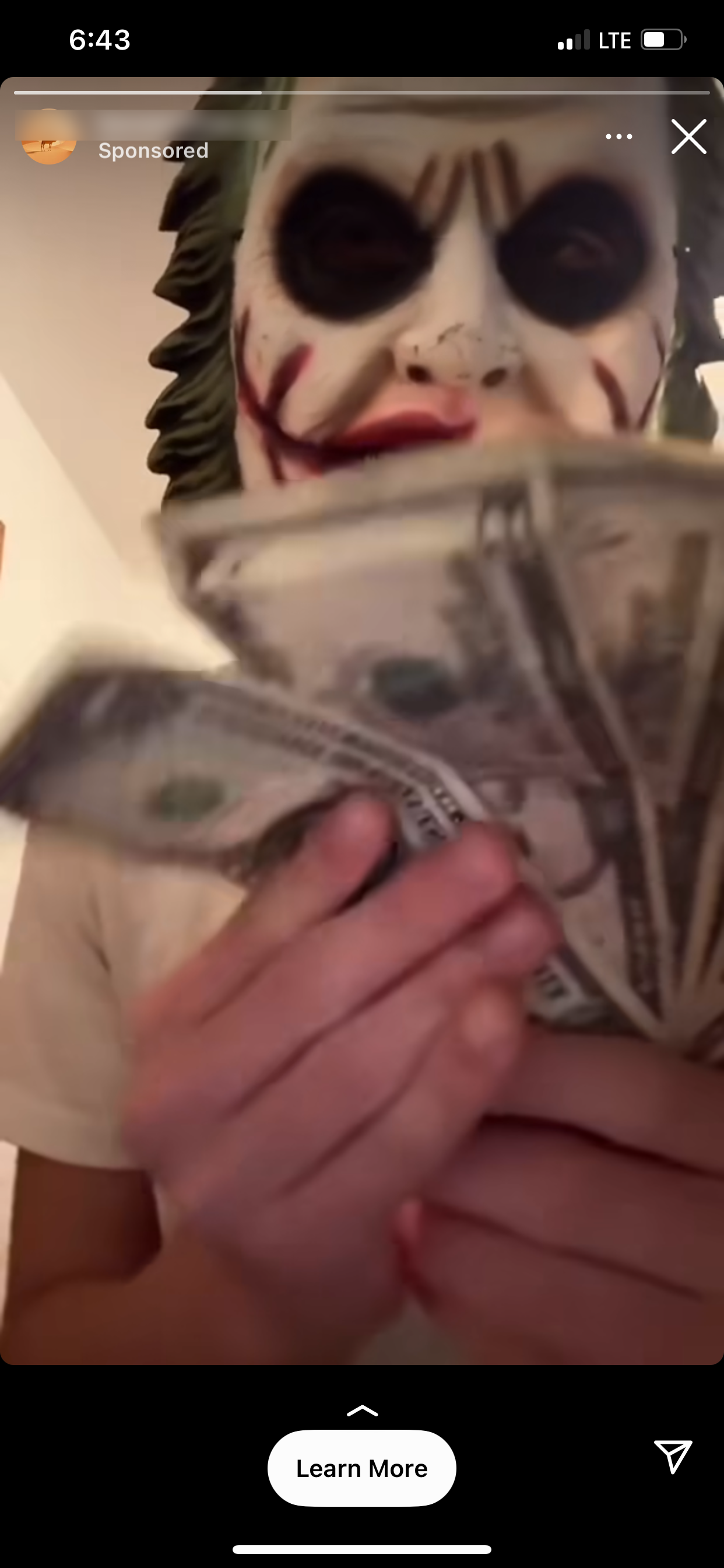

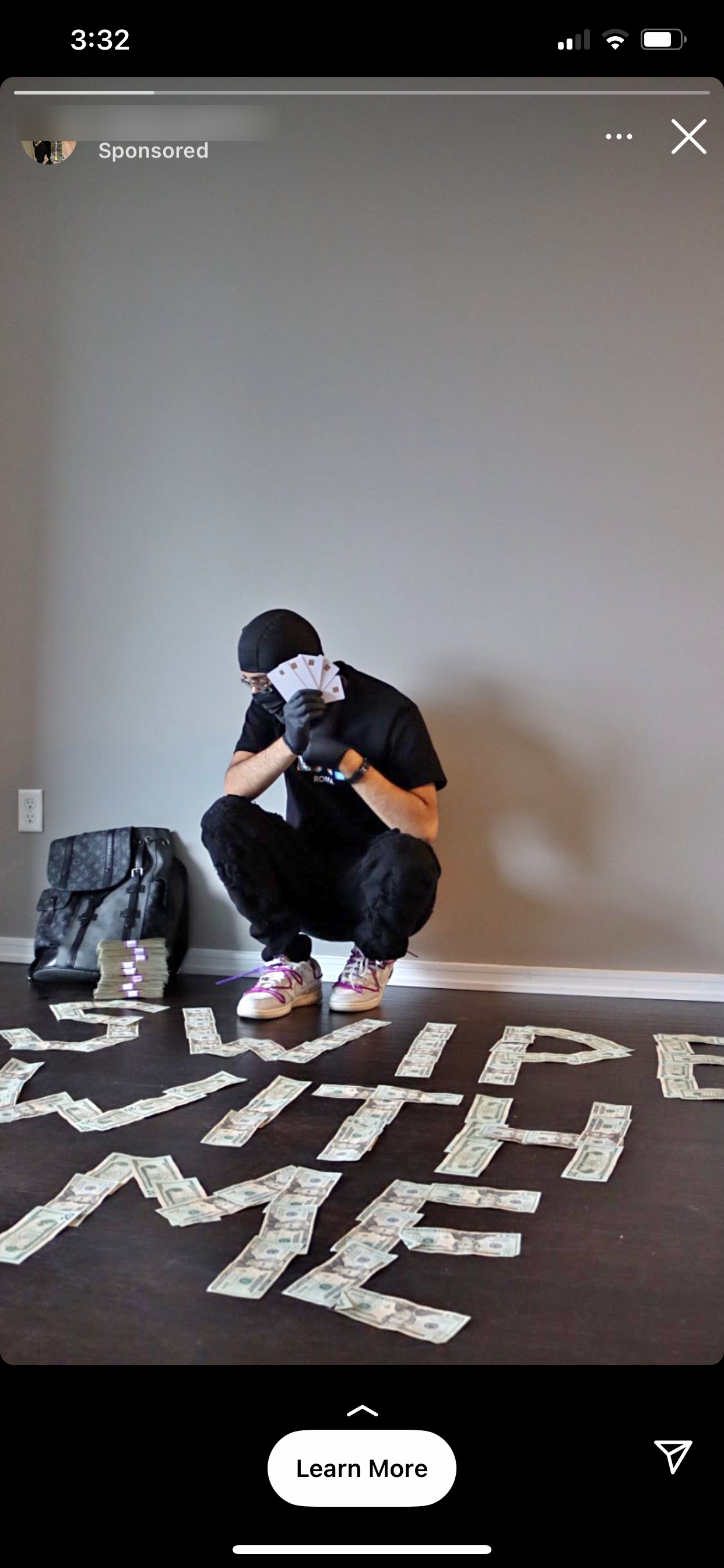

Many of these services are being advertised as part of a side hustle culture. Most of the ads I’ve gotten are of young men wearing ski masks holding gigantic stacks of cash with captions like “Take 10 minutes out of your day to learn how,” “make some bread,” “join tele to make $50k a month,” “going to eat or starve?,” “learn to make a bag,” “While some of y’all WATCHING us get RICH… EVERYONE else is TAPPIN in for the CASHAPP MONEY DROP to get RICH!” Once on Telegram, it becomes immediately clear that these accounts want to help you get rich by simply helping you deal drugs, steal people’s money, or by draining hacked bank accounts or using stolen debit and credit cards.

The ads are a window into a blatantly illegal underground economy of drug dealers, hackers, and scammers that Meta is not only failing to moderate, but is actively profiting from and injecting into users’ feeds.

“Because the harm itself isn’t on the platform—it’s a link to a different platform—this suggests Meta lacks the ability to do in-depth [analysis] of the links and solicit data from Telegram about the users’ identity,” Karan Lala, a founding fellow at the Integrity Institute, which was created by former members of Facebook’s Integrity team, told me. Lala has previously studied the prevalence of spam accounts that advertise on Meta’s platforms. “Just because it’s off-platform doesn’t mean it should be an excuse. There’s things like weed photos—that’s something that should just be getting caught. If I were an engineer on the integrity team, I would want to know why our systems aren’t catching them."

Like many of Meta’s algorithmic rabbit holes, my journey into this world started with a single, curious click. After years of being served primarily ads for surf brands, clothes, and productivity apps, I got an Instagram ad with a hooded man standing in front of a Chase Bank ATM holding a giant stack of cash: “I got half a million worth of sauce in my iCloud,” the ad’s caption said. The ad was from an account called PunchMadeDev, which was verified and had tens of thousands of followers.

Clicking through the Instagram ad led directly to a Telegram group with 78,000 subscribers, which claims to sell a CashApp “Glitch” for $200 in Bitcoin that allegedly allows users to send Bitcoin through the Cash App and get “anywhere from $7,000-$14,000” in return. The PunchMadeDev Instagram account also linked directly to a website claiming to sell all sorts of stolen accounts and hacking tools. These include logins for Wells Fargo, Bank of America, and Chase Bank accounts with guaranteed balances in them, Venmo and PayPal accounts, Cash App accounts, and UberEats accounts. They are also selling what they say are verified Instagram accounts, YouTube accounts, and Netflix, Hulu, and Disney+ logins. It is also selling a bot designed to “hi-jack all mobile phones and email addresses 2FA codes.”

“Linkable credit card with $7k-$10k balance. Attaches to Cashapp, PayPal, Apple Pay,” one product listed for $120 reads. “If you buy this item you’ll get my full support on Discord/Telegram if there is a problem!” 404 Media has not tested any of these accounts because logging into them would be illegal. A spokesperson for Cash App said the glitch being advertised is a common Cash App scam and that they are not aware of any vulnerability in their system.

I got in touch with the person running the PunchMadeDev account, but the person declined to answer any questions.

Since clicking on the PunchMadeDev ad, I’ve been bombarded with hundreds of Instagram ads for illegal services and drugs. Nearly all of these advertisements link to Telegram accounts where the drugs or illegal services can be directly purchased, though some of them go to Linktree accounts or a user’s own website that advertises these services. From these ads, I have joined 55 different Telegram servers (ads for the same servers pop up over and over again from different Instagram accounts). At one point, I was asked by Instagram if I “want more or less of your ads to be like this?” beneath an advertisement that featured blank credit cards and stacks of cash.

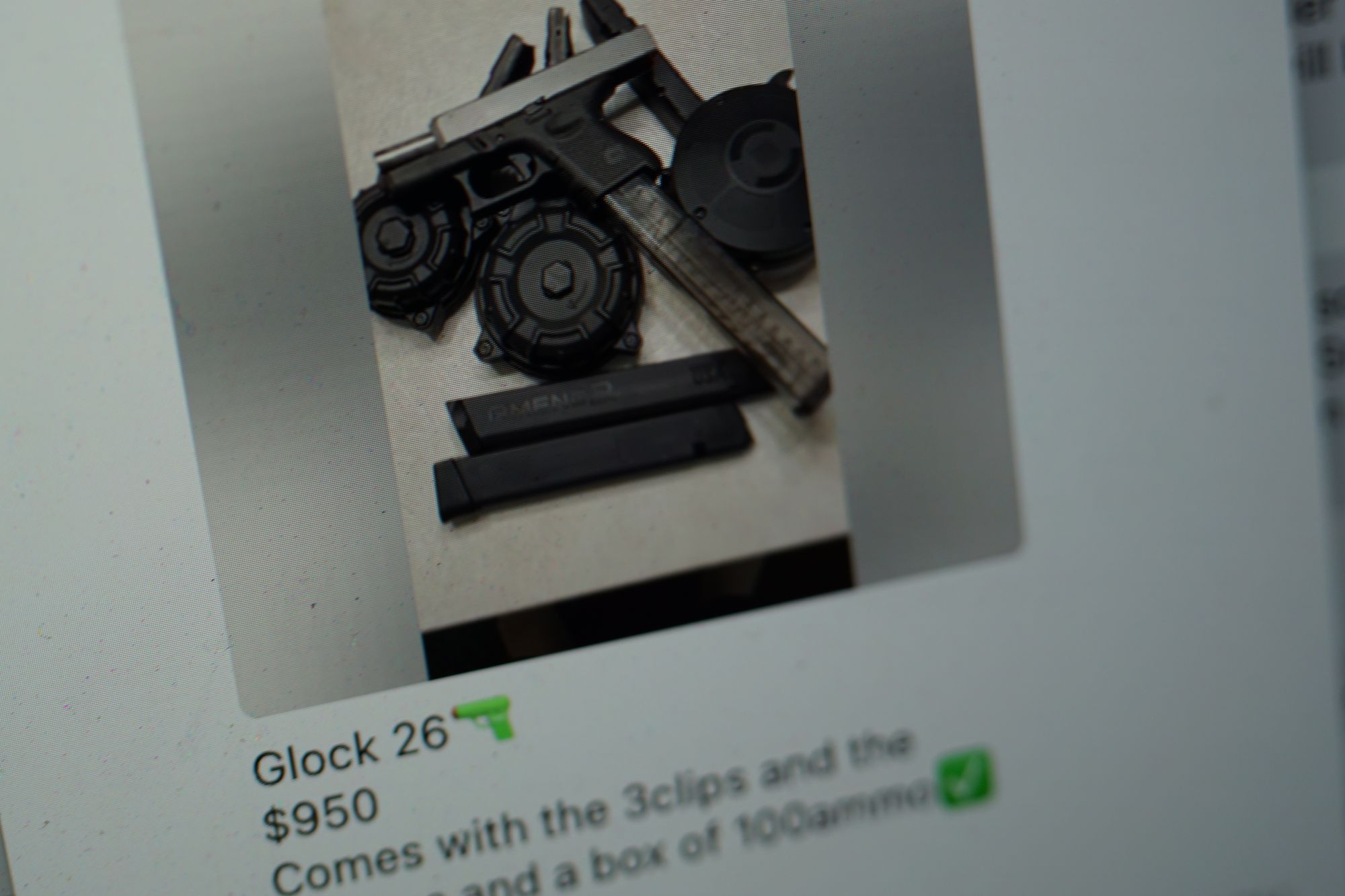

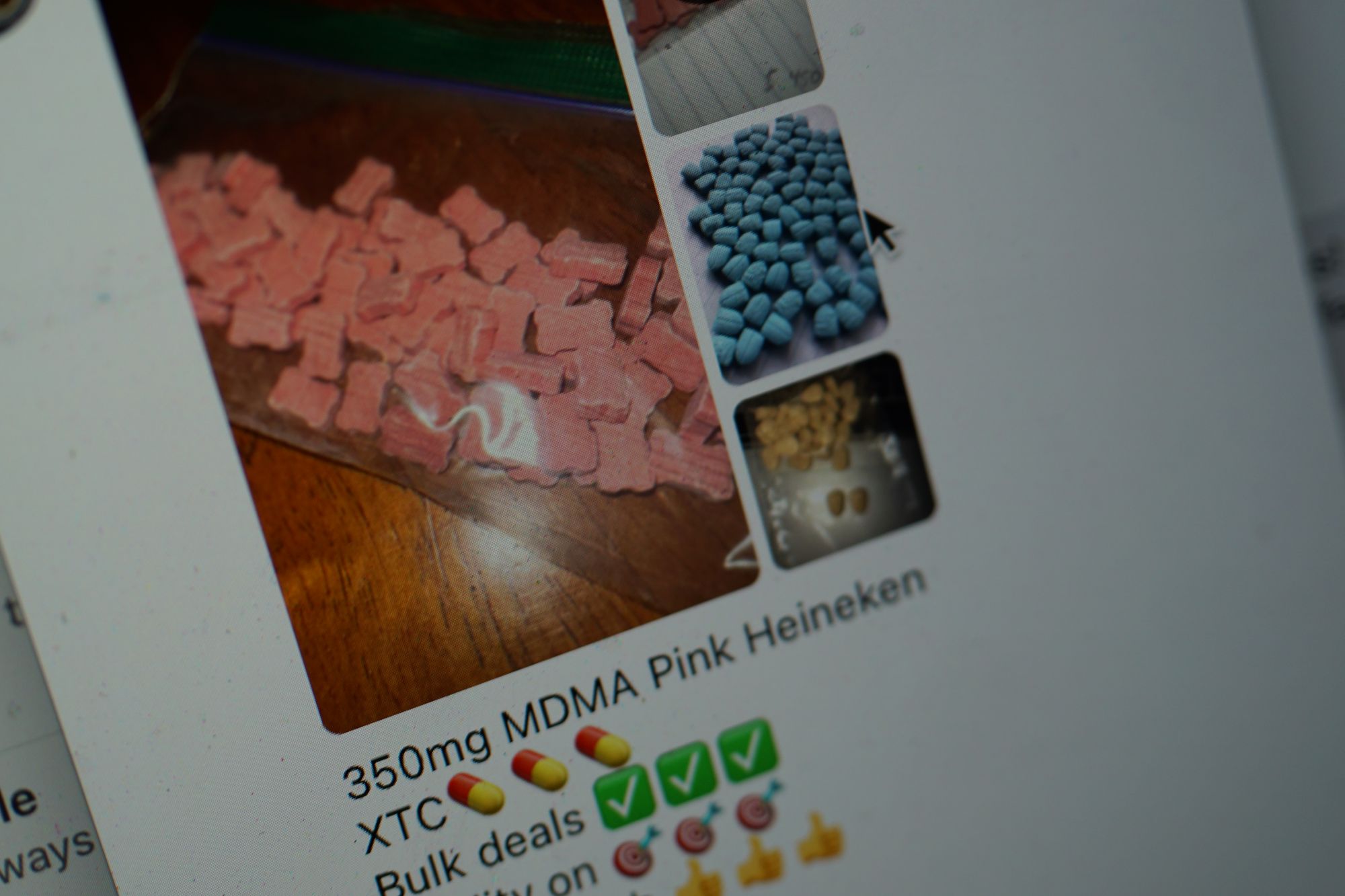

While some of the ads are subtle, many of them are not. Lots of the ads use clear language and imagery about what they’re selling on Instagram itself. I have seen ads featuring giant bags of mushrooms, sheets of acid tabs, piles of guns, ads for “counterfeit bills,” pharmaceutical bottles and huge piles of pills, and trash bags full of weed. Sometimes the usernames are gibberish or seem designed to evade Instagram’s content moderators, while others have Instagram display names like “magicmushrooms_psychedeliccs,” “medical grade pills,” “clone credit cards for sale,” and “high quality counterfeit notes.”

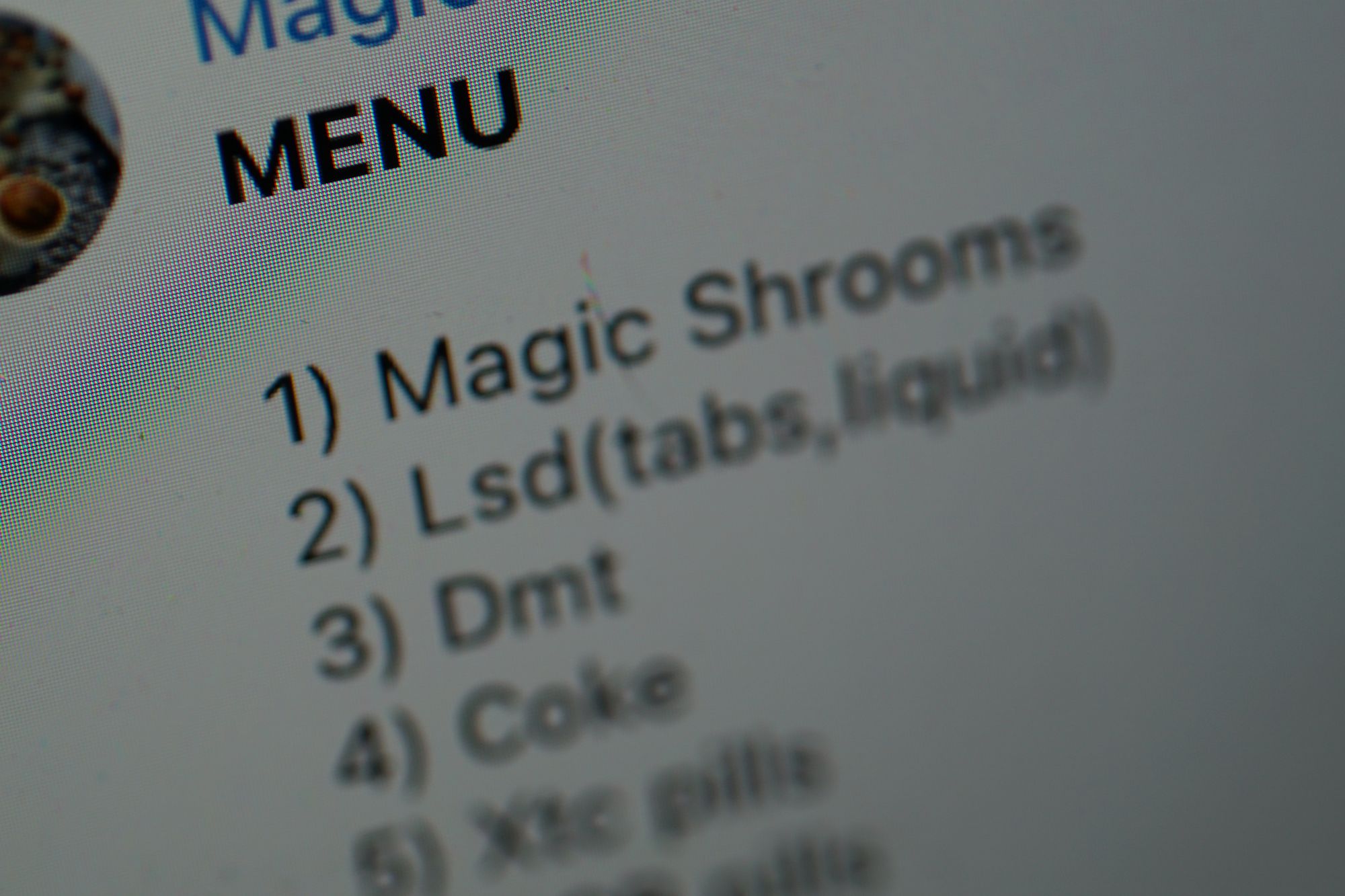

Once clicking through to Telegram, most sellers offer a “menu” of items. One, with 102,400 members at the time of this writing, sells “Magic Mushrooms, lsd (tabs, liquid), ecstasy, molly, adderalls, xanax, Dot, coke, meth crystals, ketamine, and mdma,” among others. The chat is full of photos of what the admin says are drugs and what certainly look to be drugs: “COKE (HOT), METH CRYSALS (HOT) DMT (HOT), KETAMINE (HOT),” one recent message, beneath photos of the products, said. The chat is full of instructions on how to order, videos of the products and of USPS boxes and receipts designed to inspire confidence among customers.

Another group advertises “Ice meth available in kilo weight” and has a photo of a bag of white crystals on a scale. Another advertises “ozempic weight loss injections for sale UK, France, USA, Canada.” Another advertises “AAA+ category of counterfeit money. All our counterfeits work on ATM machine, shopping centers, casinos, in malls and they’ve also bypassed all counterfeit tests. Pounds, Euros, Dollars.”

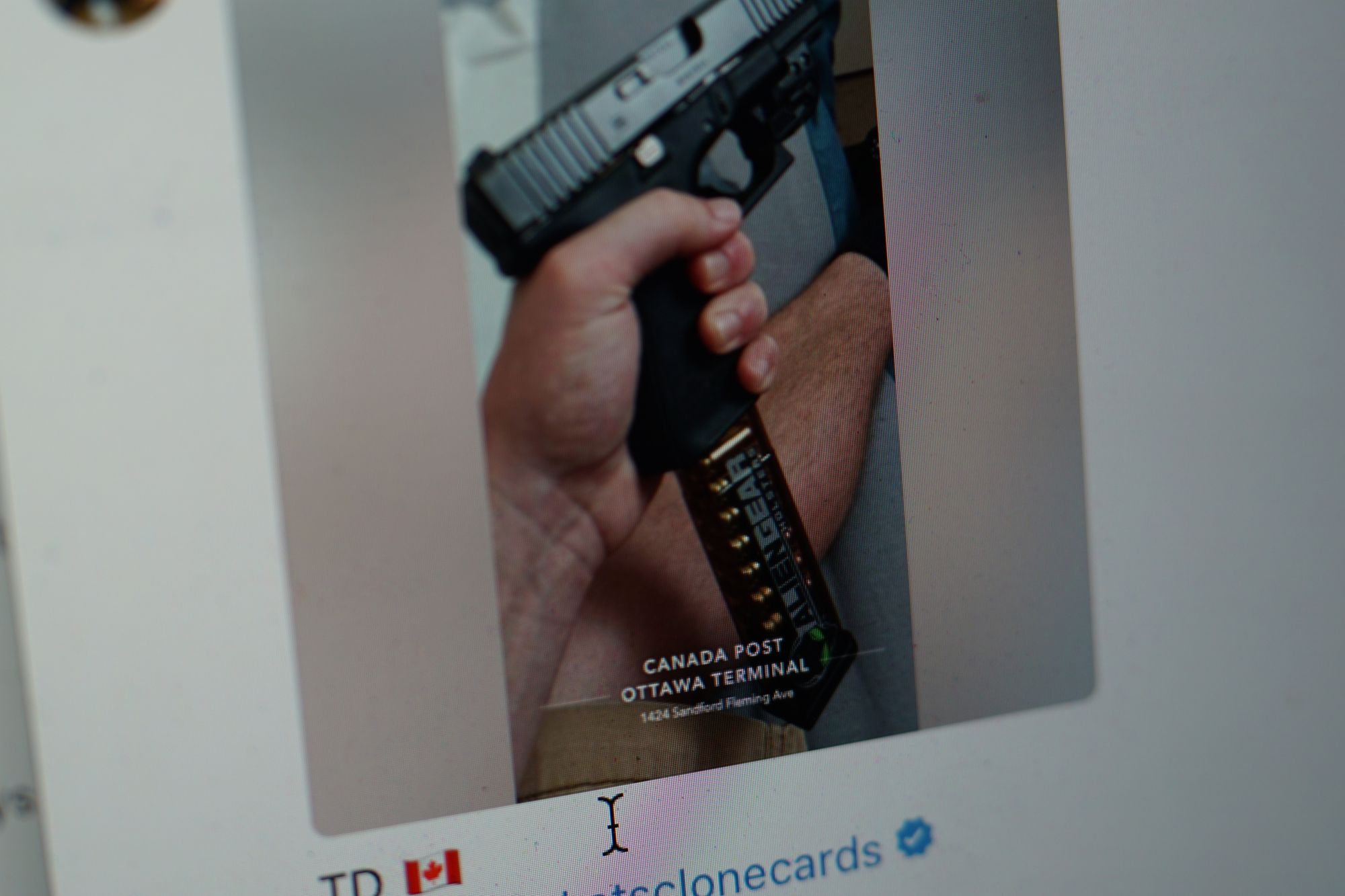

A Telegram channel specializing in the sale of guns says “hmu for any kinda glocks you need. We give them at good prices” and advertises international shipping. Successful deliveries to customers are called “touchdowns.”

A few of these servers specialize in wholesale quantities of weed, others offer only hacking services or stolen accounts, while some are illegal service emporiums offering a whole host of things. One group, for instance, sells “cloned” credit cards alongside bottles of codeine syrup, oxycontin, and silenced Glock handguns. One Instagram ad had a photo of a woman in a dress with a Russian caption that said “we are currently looking for female massage therapists to work in our salon. We offer high income ($500-1500$ per day) and good working conditions.” The next slide of the ad had a woman’s hand holding a stack of hundred dollar bills and linked to a Telegram that had been removed from the chat app for violating its policies.

I asked Laura Edelson, a researcher at New York University who specializes in social media ad spending, if there was a way of estimating just how prevalent these sorts of ads are on Instagram and Facebook, and how much money Meta might be making from them. She said that “Meta makes ads shown on Facebook/Instagram transparent through its Ad Library while they are active only.”

Edelson suggested that the large number of ads for illegal content that can be trivially found “certainly isn’t promising,” and pointed to the thousands of active ads that can be found for these types of services on the Ad Library by searching “t.me,” the link shortener for Telegram.

It’s also difficult to determine which of them are scams designed to get people to send the seller money in return for nothing and which are actually selling drugs or guns.

Sellers spend most of their time in their Telegram chats trying to prove their legitimacy. They are full of text message screenshots from supposedly happy customers, videos of USPS receipts that supposedly show shipments, and videos and photos of their products. Some sellers offer FaceTime verifications where a buyer video chats with the seller to see the specific product before placing an order, or does a FaceTime call with the seller to be talked through how to login to a hacked account, link a stolen debit card to the Cash App to cash out, or otherwise verify that what they’re buying will actually work for them.

Subscribe

“FACETIME VERIFICATIONS ONLY,” one person selling a pound of weed for $1,000 wrote in a recent chat. “WE OFFER 2 DAY SHIPPING FOR ALL OUR CLIENTS ALONG WITH INSURANCE!”

“*WE HAVE THE FOLLOWING* WEEKEND DISCOUNTS $65 DISCOUNTS ON ALL ORDERS SHIPPING VIA USPS: Magic shrooms, LSD (tabs, liquid), DMT, Coke, XTC pills, Xans bars,” another group advertised.

It’s hard to say which of these are “legitimate” and which are scams, but “a lot of drug sales have migrated from the dark web to chat messengers,” Ian Gray, a researcher at the cybersecurity firm Flashpoint, told me.

Regardless of whether the accounts are scams or actually selling drugs, guns, and credit cards, the ads shouldn’t be on Instagram under its own terms of use and are a content moderation failure.

Meta has shown no real ability to reliably moderate these ads since I showed them examples of ads from 10 different accounts selling illegal products. An Instagram spokesperson said “we investigated and disabled six of the accounts you shared for violating our policies; the rest had already been disabled.”

Immediately after hearing this, I searched again for ads from the same hacking and drug vendors and was able to find several of them operating under new accounts, but linking to the same Telegram accounts. PunchMadeDev, for example, has a series of backup accounts and backup Telegrams that all link to each other; I got a new ad directing me to PunchMadeDev’s Telegram within a day of Facebook banning the original account.

The Meta spokesperson said that “the prevalence of content that violates our Restricted Goods and Services Policy is about 0.05 percent of content viewed on Facebook and Instagram. In other words, out of every 10,000 views of content on Facebook and Instagram, we estimate no more than 5 of those views contained content that violated this policy,” and added that “Views of content violating these policies are very infrequent, and we remove much of this content before people see it.”

While this overall percentage may sound low, Facebook is one of the largest ad companies in the world and has billions of users viewing billions of pieces of content. And, like other types of content on Facebook, the problem is self-reinforcing. For the purposes of this article, I intentionally clicked on most of the ads for illegal services that I saw. As a result, a large portion of all of the ads that I have seen on Instagram over the last few months are for these types of accounts. “When you engaged with that specific ad you got, that reinforced your interest in these types of ads,” Lala said. “It looked at the profiles and characteristics of other people who clicked on that ad you clicked on and, once you start going down that rabbit hole, you just start to see all of it because of the characteristics of your engagement pattern.”

While most of the ads I got were in my stories, a few of them showed up in my normal Instagram timeline. Two of those posts had stats on them: One ad had 2,484 likes, the other, a video, had 21,622 views.

Lala said that Meta faces what seems to be a high “recidivism” rate with these sorts of ads. Meta bans the ads and the accounts posting them when it becomes aware of them, but new accounts keep popping up, and they keep managing to get through the ad approval process: “The cost of taking down an asset is so much higher than the cost of creating a new asset,” he said.

There’s another major issue here: Even if these ads are seen by a relatively small number of people, there is no incentive for the people posting them to actually stop. Once someone joins a seller’s Telegram chat, the seller has the ability to reach that person indefinitely with or without Meta, because Telegram itself does very little content moderation. That means that each new Instagram ad leading to a Telegram chat might have the ability to get the seller a few new prospective customers, and being banned by Meta doesn’t actually harm their actual business of selling illegal goods on Telegram.

“In order to prevent this kind of harm, you have to identify the link is malicious at the ads review process and before there’s any traction,” Lala said. “It can’t be that you have some traction then it gets flagged.”

After analyzing some of the accounts I sent him, Lala speculated that the people buying these ads are cycling through burner phones, using VPNs, and doing other things to make their ads and their alt accounts more difficult for Facebook to detect: “You create an account on a $50 burner phone, use it until it gets blocked, then move to another device.” He also noticed that a lot of the accounts running ads were months or years old, suggesting that sellers are making, buying, or hacking accounts, letting them “mature,” and then “doing more high-risk activities with it.” They do this because Facebook is likely to put more scrutiny on ads from new accounts that could have been spun up specifically for this purpose.

I have regularly covered Facebook’s content moderation, and have pointed out how difficult it is to moderate the posts of billions of users from nearly every country in the world in a variety of languages and from a variety of different cultures. While it’s true that content moderation is difficult, there’s a difference between allowing someone to post links to drug marketplaces on the platform and actively selling ads for these marketplaces and injecting those posts directly into user’s feeds.

Previous studies have found that Facebook’s ad marketplace has vulnerabilities. Last year, for example, a joint study between Global Witness and NYU’s Cybersecurity for Democracy found that “Facebook either failed to detect, or just ignored, death threats against election workers contained in a series of ads submitted to the company.” That study also found that YouTube and TikTok more consistently rejected or quickly removed the researchers’ test ads.

This year, Meta has laid off large portions of its staff, which has also affected teams that do content moderation.

“Unfortunately, this might be a consequence of the recent layoffs in Trust & Safety that Meta has made. Security is an ever-evolving game, and Meta may just no longer have the resources in place to keep up with the tactics bad actors are using to get around policy enforcement,” Edelson of NYU said. “In this case, advertisers are directing users off-platform. Facebook used to have fairly sophisticated detection of this kind of activity, but the volume that a trivial search is turning up right now indicates that may no longer be the case.”