I learned how to read by reading Baltimore Orioles game recaps in the sports section of the Washington Post. I remember sitting on our couch as my dad pointed to words like “Cal Ripken” and “Mike Mussina” and “baseball” and “Orioles,” which, at first, I wasn’t exactly reading but was guessing from memory because we had watched part of the game on TV or because, even then, I knew the names of a lot of the players from baseball cards my dad had bought me. This is one of my first memories. I was not in school yet and was probably three years old.

When people ask me why I became a journalist, for a long time I didn’t really have an answer. “I didn’t want to sit in an office all day,” I would often say, even though that is exactly what I have mostly ended up doing. I do not know why it didn’t occur to me until after I had become a journalist that one of the main reasons I went into this line of work is because my dad spent 30 years working at the Washington Post, is very proud of that fact, and brought the newspaper—and very dirty, ink-stained clothes—home every day. My dad worked in the press room, first working overnight running the gigantic, four-story machines that printed millions of papers every day. Later in his career, he did maintenance on the presses, working from 4 AM until noon. I was talking about this with a friend the other day, and it occurred to me that I am not really sure when he slept. One time, a gigantic printing press roller fell on his head and caused a herniated disc, which he needed surgery for.

On historic days—presidential elections sometimes, but mostly when DC won the Super Bowl and Cal Ripken broke Lou Gehrig’s consecutive games streak, he brought home the metal “plates” used to print the newspaper. He taught himself how to mat and frame these, hung them up on the walls of our house, and sometimes gave them away to friends and family. He told me stories about how Donald Graham—the then CEO of The Washington Post and son of the legendary Katharine Graham of Pentagon Papers/Ben Bradlee fame—would sometimes come to the printing plant and tell them that they were doing a good job. He was proud that Graham seemed to know his name. He worked on Christmas and Easter and the Fourth of July and when there were blizzards and one time got stuck in traffic in the middle of the night because the circus was in town and elephants were crossing the road. He went back into work on 9/11 to help run a special afternoon edition of the paper. I do not think he has been late for anything in his life, which I assume is a result of working for decades at a place where the newspaper must come out every day, without fail, no excuses, and where the printing presses needed to work always in order to hit the Post’s circulation numbers.

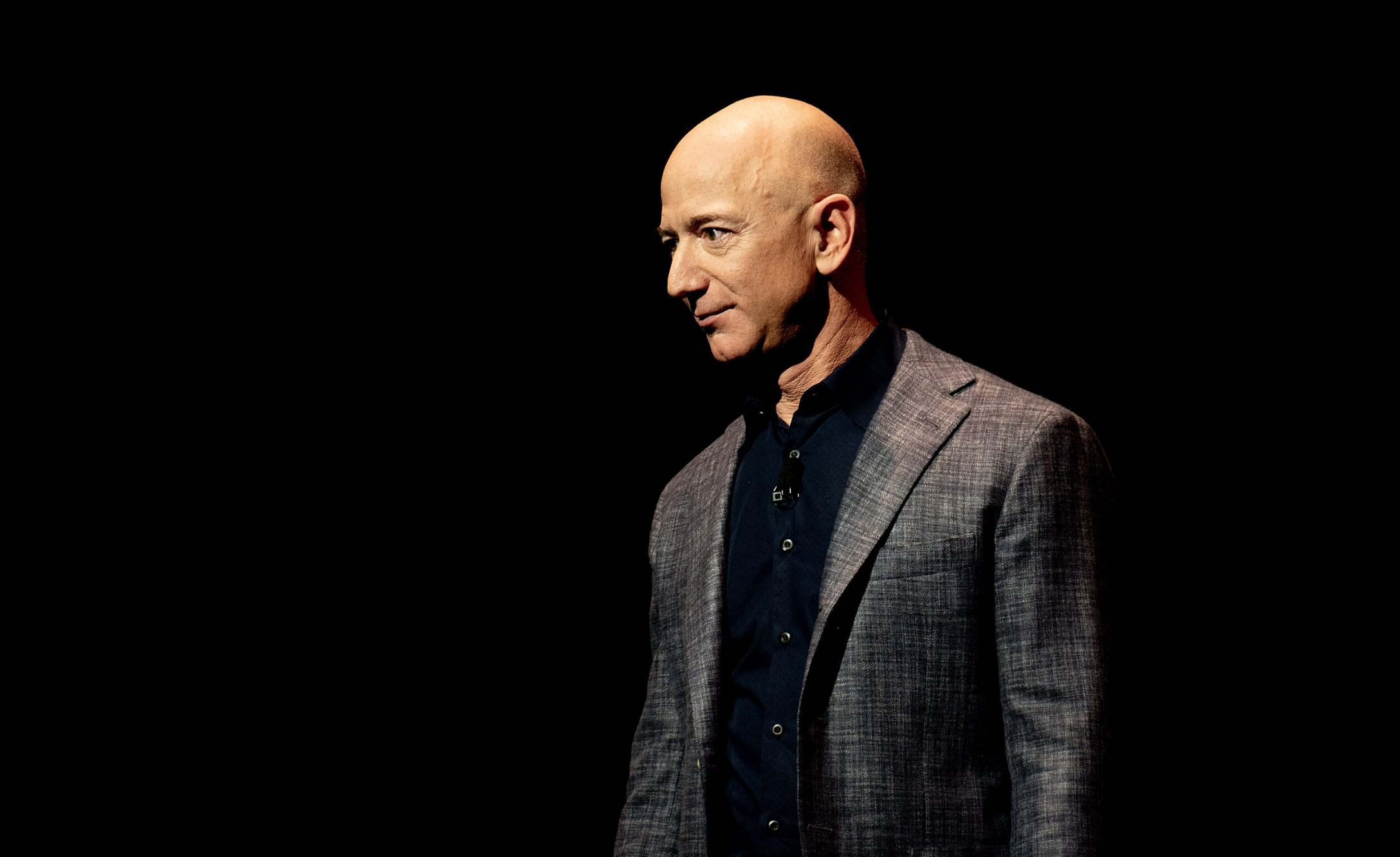

The current owner of The Washington Post, Jeff Bezos, one of the world’s richest men and the current ‘Adult in the Room’ recently made what he described as a brave and shrewd business decision to win back reader trust. This calculated business decision has, famously, made 10 percent of the Washington Post’s annual revenue evaporate overnight and has led 250,000 people and counting to trust The Washington Post so much that they canceled their subscriptions.

Much has been written about Bezos’s decision to kill the Post’s endorsement of Kamala Harris, and about his unfathomably stupid and farcical op-ed defending that decision, in which he writes “I challenge you to find one instance in those 11 years where I have prevailed upon anyone at The Post in favor of my own interests. It hasn’t happened,” seemingly unaware of why he was writing this op-ed in the first place.

The aftermath of this disaster has led many of the Post’s reporters, who do good and valuable work (including brave work on the actions of their owner), to understandably ask people not to cancel their subscriptions, or to suggest that people cancel their Amazon Prime subscriptions instead, because if the Post is not profitable, they may lose the resources to do their jobs. I don’t wish for anyone to lose their jobs and I want the Washington Post to continue to exist. I want the talented journalists who work there to be able to continue to do their work, whether it is at the Post or elsewhere.

But the truth is that Jeff Bezos is a man who has made his wealth by extracting an unfathomable amount of value from his employees and by running ruthless workplaces. At Amazon corporate, in Amazon warehouses, and in Amazon delivery vans. He has amassed so much wealth that 250,000 people or 2.5 million people canceling their subscriptions to anything he owns is not even a rounding error. If he wanted to, Jeff Bezos could keep the Washington Post in operation indefinitely with zero subscribers, forever. The Post is not making a profit right now and it exists at the moment in the way that it exists because Jeff Bezos can afford to take a loss on his Washington Post side project without batting an eye and currently feels like doing so.

We have seen over and over and over what happens when billionaires decide to exert their will on the prestige publications they decided to buy on a lark, and we have seen what happens when they lose interest in their side projects. It is never good for the people doing the work there.

When I became a journalist, I thought that I wanted to work for The Washington Post, just like my dad. Then I went to work for VICE, and made working at VICE part of my identity. I wanted the company to succeed so badly because I believed in what we were doing and I believed in the institution. I worked zillions of hours of unpaid overtime, took on side projects, canceled vacations to do work, worked on vacations, and made incredibly hard decisions, thinking that, if I did my job well enough, the company would succeed and we would get to keep doing what we were doing. I spent the vast majority of that time doing work that made money for an over-bloated apparatus that existed to make a bunch of middle managers and executives large salaries and bonuses and to benefit a founder who is now retroactively denigrating our work in an attempt to cling to whatever relevancy he can find by catering to conspiracy theorists and the right.

My dad worked first in southeast DC, then in the brand new, massive printing press in College Park, Maryland near our home. When that shiny printing press shut down because circulation diminished after the internet became a thing, he worked for a few years in Springfield, Virginia. Growing up, a huge part of the mental conception of my dad and who he is was “he prints The Washington Post.” And then, one day, he didn’t work there at all. My dad took one of the many, many rounds of buyouts that hit The Washington Post, and now he works somewhere else. He doesn’t talk about the Post now much at all.

My dad worked at the Washington Post for 30 years. It was important to him. And then he didn’t work there anymore. And now it’s not. VICE was very important to me. And then I didn’t work there anymore. And now it’s not.

It has been very easy for me, mentally, to leave behind a place where I made money for a Board of Directors who made decisions about my life and my work without thinking about me or my team as human beings, who got paid much more than me, and who are showing at the moment that they do not actually care about journalism at all.

The Washington Post is probably not going anywhere and on some level we need large journalistic institutions to continue to exist. But even well-run large outlets are surely full of waste and bloat that are funded on the backs of and at the expense of the actual journalism. The “wealth and business interests” of billionaire owners, as Bezos writes, are not a “bulwark against intimidation” for journalism. They are, themselves, the biggest threat.

404 Media is barely a year old and we employ four people. You cannot compare our business or what we have done to the Washington Post. As our friend Molly White explained last week, “Just Go Independent” sounds good in theory, but it is not necessarily easy. Doing high quality, investigative journalism is hard, and it is expensive. But it’s not that expensive, and the infrastructure to do it on the internet is getting cheaper and easier to pull off. Printing presses, middle managers, fancy offices, and executive salaries are the expensive things, and they are unnecessary.

Still, it’s unclear whether “Just Go Independent” is a sustainable career path for the number of journalists who we need to have a functioning society. But I do know that relying on the passing interest of billionaires to keep journalism alive is not sustainable. And I know that 250,000 subscribers could fund a lot of independent journalists.